2. A Letter to Blood

Dear M

I’ve been thinking about your title ‘Blood’: so innocent and candid in its base simplicity but so visceral and dangerous in its threat. Is it a metaphor and metonym in one? I read on Twitter there was a fire in the basement of the gallery your film is showing in, which seemed to sum up the same epigrammatic explosion configured by that single word.

Blood.

Weird how a word can be so messy in its image but so clean and complete on the page.

I wonder what will happen if I write to the work instead of you? You wrote a girl with ‘strong emotions… welling up inside’, and now I’m going to write to her and the script she moves in, as I’m watching her. This kind of writing is like touching, it happens that quickly, an intimate meeting of word and image. My hand (my bodily signature) dances about the keyboard; it touches the machine and types what wells up inside, from letter to letter, like a scene change.

Yours

A.

*

Dear Blood

Of course you begin with a red building, B. You abject Bloody Chamber. A rectangular concrete shell that pulses with colour, as rosy and sore as cow meat. I can tell you’re a film about childhood because there’s a mickey mouse painted on the outside wall.

But it looks cold up in those mountains, as if my veins would go blue there. Do vampires live there? What about wolves? I tend to write down authors names and books I’ve read when I experience art, as a way of thinking into it when I’m stuck or confused. So I wrote down ‘Angela Carter’ and the catch-all phrase ‘Magic Realism’ when I watched you the first time, as you open with a fairytale landscape of schoolchildren reading from M’s script in an Eastern European accent. My bag is heavy / and my feet are tired. At least these kids are wrapped up warm. They’re helping each other learn to read, orally, but leading us through the story too, like the comforting chant of a night-time chapter.

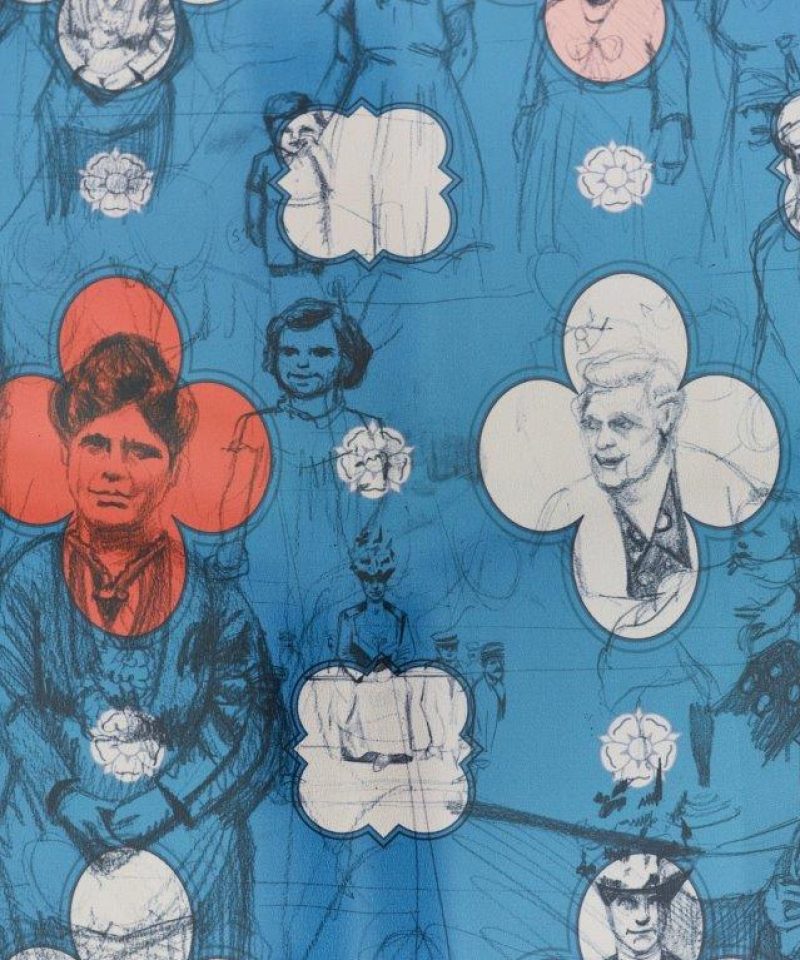

I see Isabel is back; she was in The Udder when I saw her last. But what’s she doing with a sieve on her head? Is it a helmet of domesticity? She is a GIRL, after all. Power to her for asking: Why am I being punished? She holds the hands of an imagined twin, and spins around in a circle. One is dressed in an English country gent’s tweed coat, while the other Isabel is rocking Albanian housewife in a blue woolen dress, embroidered waistcoat and floral headscarf. Blood, your phonetic parts flash up on screen: B L O O D – the caption to Isabel’s tricksy face and dragged up dance. I start to wonder if you’re not so much a film about death (as the title first implies), as a film about life, of living it differently in whatever clothes you choose.

Soon we are up her nose. I’ve been thinking about these scenes. First we meet Isabel’s two friends making pinkie promises in pink pyjamas, begging her to play. They spin her round. Isabel finds respite in the giant black nostrils of an even bigger fake nose, but her frenemies follow her, as they double up as the skin-munching antibodies that are causing Isabel’s nasal infection. I bet she’s faking it, they say, pointing towards the fictional infrastructure of the fairytale we are watching. Tell M, when you see her, that was clever.

Isabel appears vulnerable in her hospital gown. I wonder if these scenes of you, B, are a comment on the fragility of the female body. The blonde girl is sick, scared, and soon to wither even more as her nose gets bloodier than a playground nose bleed (which, come to think of it, is always pretty embarrassing). And so I guess what I’m asking you, Blood, is this: is the embarrassing exposure of Isabel’s disease, her corporeal failing and fucked over turbinate bone, some sort of willing tactic on M’s part? The turbinate is supposed to clean and filter the air that we breathe in, so the doctor tells us, but Isabel’s is faulty. She is a messy and smelly, sick young thing (invariably described as a monster; a poor creature; a foreign body), rejecting the pre-inscribed femininity that has been mapped out before her. The pink patrol speaks a language of digital girlishness (full of Lols and Seriouslys), but Isabel’s language is infinitely more wayward. She wants to escape the polyester pink and replace it with red.

It makes me think of Virginia Woolf making hallucinogenic stories out of her sickbed in the self-referential essay ‘On Being Ill’; or Dodie Bellamy, who made the expression of neuroses (and blood) a feminist literary form in The Letters of Mina Harker. Dodie later wrote about the strategy in a separate essay called ‘The Cheese Stands Alone’: ‘In my gusto for exploding the boundaries between my writing and my lived experience, I was determined to push the personal into ever more embarrassing realms.’ Sickness might mean blood, but sickness also means power: it means transgression. It pushes the body (and mind) into unchartered territories.

Quite literally in the case of you, for the next minute we’re in Albania. A river flows across the base of the screen, while a mountainous condensing landscape is stratified across the top. It’s an image of that other life-enforcing element: water. In M’s magic realist tale, the Albanian narrative represents Isabel exploring the depths of her unconscious, enhanced through sickness. She is both in and out of body during this moment of abject rupture, which provides the necessary environment for transgression and desire. She has not only run away from home (and all of the domestic trappings that that entails) but is also seeking out an alternative, of how one might be a girl, and what this might mean. What it could mean. She is literally in battle with her own flesh and blood.

I think the next subplot is really bold of you, Blood. It’s a story of transgenderism, transgression, of passing and difference; but it also reveals the extremes of such circumstances, and in this sense is also a story of female oppression, domesticity and chastity, contained in a vessel that is part fiction and part document. I hear the research behind you is drawn from the anthropological findings of Antonia Young’s Women Who Become Men, which I read in the British Library last week. First, it was Edith Durham that struck upon Albania’s sworn virgins in the mid 1860s; then in 1919, while reporting on the situation of refugees after World War One, the American journalist Rose Wilder Lane also delved into similar ethnographic detail. Rose was the daughter of Laura, the author of Little House on the Prairie, which I thought was a funny coincidence given M’s warped vision of childhood innocence.

I am wondering how M met Lali, for your credits confirm that s/he is playing a version of hirself. It is real life and real speech reoriented by the permeations of film and fiction and dialogue and writing. Lali introduces hirself to Isabel, explains that s/he chose to live hir life as a man, in exchange for eternal chastity. But if the promise is broken, the sin can only be repaid with the sinner’s blood, reaping shame on all hir family. Antonia wrote a piece for Cosmopolitan on the sworn virgin tradition, but it was the 1990s – the era of the sex column – and the editors tampered with its language, preferring to emphasise the sacrificial element of the task, as opposed to it being a positive redeeming choice for many (as well as the conditions of that choice).

I wouldn’t change it for anything says Lali to the bewildered interior Isabel. Meanwhile, the girl’s exterior continues to bleed, straight from the nasal cavity; she’s rejecting those bones and singing back to the infectious mites with finger-wagging rhymes, as her friends also draw on her face with lipliner.

In contrast, Lali takes an extended drag from a cigarette and later sips at some liquor while talking about football. What a man, what a man.

Blood, I am starting to think that you are a film about multiplicity, of being more than one thing at once, as Lali, in white cone hat, plaid shirt and smooth mountain skin says, I am a he and a she. Cosmo failed to note the overwhelming differences between glossy clit culture and rural Albania. M does not, as she gives voice to the protagonist in Lali, in dialogue that feels incredibly honest, even if the set-up is not and the cameras are on hir. In answer to Isabel’s sassy claim (I don’t need to be a man to be free), Lali simply states: Your life is different to the one we had…

And as Lali takes care of the wandering Isabel and invites her to sip from the very same liquor, her face becomes crusty and deformed. She is a red raw female grotesque with suffering skin, but in the alternative fairytale land of Albania, she is testing out the limits of her messy feminine identity (emotional, sick, intersectional), just like Wolf-Alice in The Bloody Chamber or Kathy Acker in Blood and Guts in High School. Blood, I wonder if your elemental freedom stems from the fact that you are fiction. The fairytale lends itself to a rewrite.

Your Isabel with blonde Rapunzel locks is pre-adolescent and pre-woman. She is also delicate, diseased and defective. But herein lies her revolting potential. She is in a marginal state, hospitalized but also moving; it is a frenetic state of being and subjectivity in which change and transgression can occur. When she runs away from Lali’s cottage to the tower, she’s not only running away from her fairytale foster parent, or running away from her failing nose; she’s running away from her old SELF and healing, this unrecognizable poor creature. But with this transformative cleansing comes BLOOD, as the young girl confesses in the closing sequence: At that moment strong emotions were welling up inside me. There was moderate bleeding from the nose and mouth. The odour was very very bad.

*

A postscript for M:

I wrote a letter to your work, as excessive and scrolling as Isabel’s blood-sucking gauze, because I thought this the most intimate form of writing about it, given its affirmation of the visceral body. An epistle is often stained with blood as well as ink, a hand-stamp of its writer. There’s no blood on this blog, on this shiny screen. But there is feeling. I wrote it in a dazed state, a foreign body, like Virginia Woolf on her sickbed.

Blood by Marianna Simnett was commissioned as part of the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ currently showing at Jerwood Space. The Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me’ are a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and FVU in association with CCA, Glasgow and University of East London, School of Arts and Digital Industries. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.