Bada Song was born in Korea and moved to London in 1997 to study sculpture at Camberwell College of Arts. Last month she was awarded second place in the Jerwood Drawing Prize for Ta-iL, a collection of images depicting traditional Korean roof tiles. Here she talks to Jessica Lack about the inspiration behind the series.

I was born on a beautiful island called Jeju, in the southern most part of the Korean peninsular. It is famous for three things; women, black Basalt rocks and the wind. My mother used to be a skilful diver who collected shellfish and other valuable things from the ocean, and our house was right in front of the sea. There was no beach, just black rock, from which my mother would dive, and as a child I would watch her from the shore. I have this vivid memory of an incident that happened when I was about two or three years old. There was a great storm one night and the roof of our house blew off into the ocean and floated away. This memory stayed with me and developed a kind of mythical status in my mind and I never spoke about it to anyone, but I would dream about it all the time. A few years ago I was talking to my mother and I mentioned the storm and the roof escaping. My mother said “What are you talking about?” It wasn’t true.

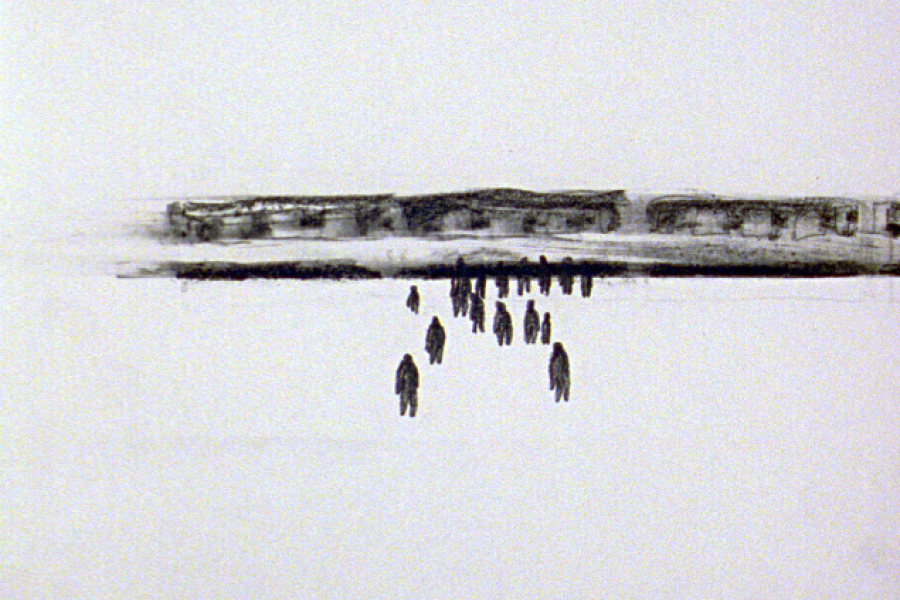

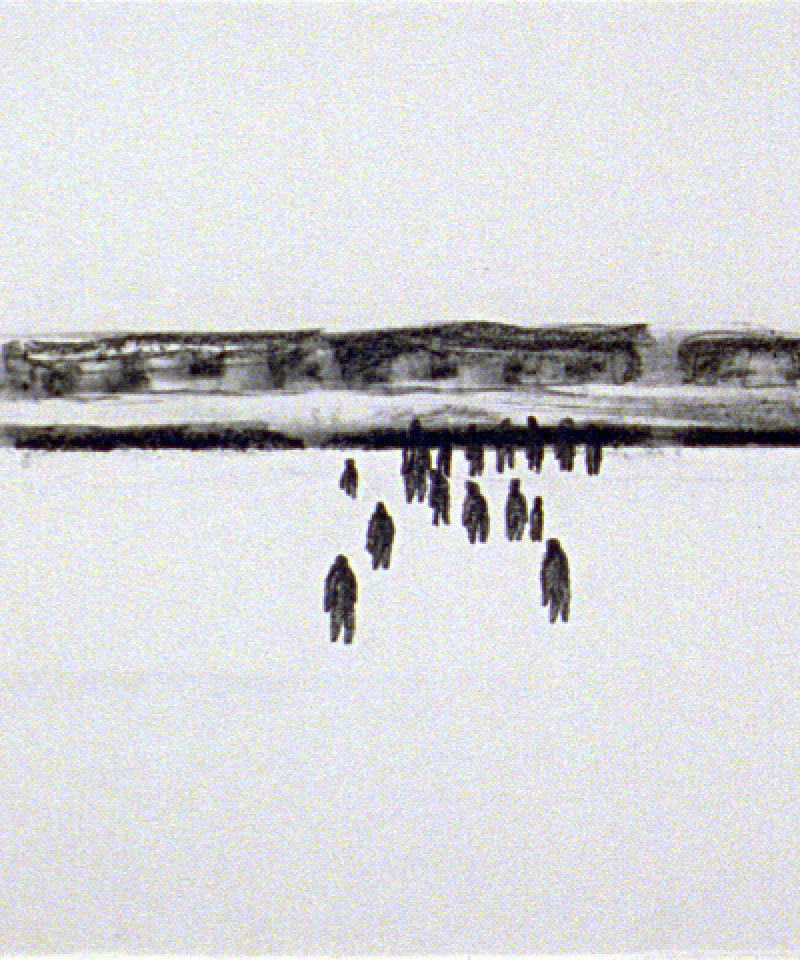

So I began to incorporate this strange dream I must have had into my practice. The first thing I did was to make some etchings of Korean traditional roofs floating in the darkness. Then I discovered a little fishing village called Jeoksung in Busan in Korea where old roofs have been resurfaced and repainted repeatedly over a long period of time. The paint is now so thick that all shape has been lost. Earlier this year I took my first trip to New York, and what I saw was a roofless city, all the buildings have flat roofs. This was enough to consolidate my practice.

I chose graphite as my material not only because it echoed my memory of moonlight glinting on the tiles of my roof in the black water but also because it reminded me of another story from my childhood. Outside my school there was an old man who sold pencils. They were all different sizes, and he would sharpen them until the lead was very long. He would then throw the pencils, point end down into a piece of wood, to show us just how strong the graphite was. I always wanted one of these pencils and when I had one I would sharpen it with a razor blade. When the pencil got too small to hold onto, I would push the end of it into the casing of a biro, so that I could use it until it was nothing more than a stub. I still sharpen my pencils this way. It is something that is part of me and integral to my practice, just like the dream I had of our roof all those years ago.