I caught up with Nikolai Ishchuk via email to ask him some questions about his work. The Family Politics exhibition will be closing this Sunday, so catch it while you can. Next week I will be posting one more interview with from one of the participating artists and a brief reflection on the exhibition in the form of a short photo-essay. You can see more of Ishchuk’s work here.

What was your route into becoming an artist – was there a moment or influence that catalyzed this decision?

I was growing up a very creative child. My parents enrolled me in a creative development pre-school program, and I did everything from drawing – I don’t think I was ever good at the figurative stuff, but I’d be praised for my sense of color and composition – to radio. And I kept at it for some time, taking more classes and such, and then I stopped abruptly when I was about 14. Perhaps it was the environment. Children in Russia used to leave school a little earlier, at 16-17, so at 14 you already had to start thinking about university. In the tumult of the 90s, no-one considered arts a career, bar a few crazies. (Even though deciding what you want to be and sticking to it at 14 is clearly crazier still.) So I went to study Economics and Sociology thinking I’d probably end up in finance or consulting. I was good at it too and got a First. I then did a Masters in Social and Political Science, quietly dropping most of Economics, and, following that, I was finally out on the labor market. Finding a job and sorting out permits took over half a year. I decided to do a short photography course at the old Central Saint Martins in the meantime so as to have some structure. (My friends kept telling me that I was glued to my camera.) I learned how to print and was hooked. By the end of the course, I landed a job in business conference production, hardly my top choice. I took another course, in the evenings, which happened to be with the same tutor as the first one. And then… there were some changes at the office, my probation was about to elapse, I was growing increasingly listless, the tutor kept saying I should give it a shot, I was mounting a self-prouced show of early work (cringe) at a cafe in Soho, and it all converged at this point where I walked into the office one morning and thought: ‘This for 40 more years? I don’t think so.’ I called my parents and asked whether they’d mind awfully if I were penniless for the next few years while cultivating my creativity. They said no, which I suspect they’ve regretted ever since until about a year ago. And the rest has led to this, and now the hole is too deep to stop.

In terms of Offset, could you quickly explain the process of how you make the work? I’m still confused as to how they are made – they seem somehow symmetrical and the title refers to a procedure on Photoshop?

The logic of it isn’t really complicated. Imagine digitally splitting an image down the line running through the middle of the couple/family, then swapping these two parts around. That’d be the Offset command in Photoshop.

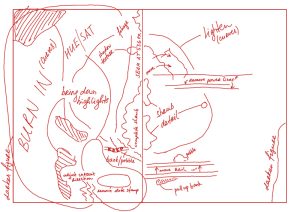

Then it goes kind of like this:

What struck me immediately on encountering the work was the lack of ‘centrality’, the figures (due to the way that they’ve been manipulated) are on the margins of the image. This seems significant – when we think of family portraiture the figure is often in the middle, they claim the image – where as your work, it seems ‘wrong’ – like a mistake somehow – I was wondering whether you could expand on this?

Making the ‘wrong’ kind of pictures that lead you back to the ‘right’ ones was exactly the point. When you flick through a family album, it doesn’t seem odd in the least that, one after another, you see a hundred pictures with the figures bunched up in the middle. But create a different formal composition, repeat it incessantly, and suddenly the whole thing seems highly suspect.

Also, when we see both the digitally manipulated images alongside the silhouettes – there is a dramatizing of the relationship between the figures – we become more aware, I think, of their gestures – you get this in John Stezaker’s early work – the negative space around the figure becomes really important – what are your thoughts on this?

Yes, you’re probably right about that – dramatization. With the reworked pictures, I think the first instinct for the viewer is to still want them to be about the people. But, because the eye can’t lock on both edges at the same time, it ends up crossing and falling into the gaping hole of a center. You end up looking through the figures at… something. The series started out as just images, but I was struggling a bit with how to emphasize that it’s not just the couple anymore but the couple and this third thing smack in the middle that has been made visible with a simple gesture, really. This is how the cutouts appeared. Speaking of Stezaker, a lot of whose work I love, my first few mock-ups for the series were of this ‘crude’ variety, but it just didn’t seem like that went far enough.

How important for you are these images are ‘found’ – in that the represented figures are anonymous to you?

AND

I was interested in what you say about the family album being a ‘cover up’ – the myriad narratives that it conceals (as much as reveals) – I was wondering whether you would like to expand? I was thinking that these images become cyphers – or archetypes perhaps. We skip over the specifics and start to recognise parts of ourselves in them.

I don’t think I can answer this one without simultaneously answering the question about the ‘cover up’… The images’ being anonymous is precisely what allows them to become archetypes, or something akin to that. I know ‘them’, you know ‘them, everyone knows ‘them’. And exactly, I didn’t want the series to take viewers on some kind of fact-finding mission and leave it at that. I’d like to think it will make them look at how they consume the narratives at which they themselves play a hand constructing. When you browse your old ‘happy times’ albums and everyone is smiling, but you recall the times actually being rather shit, what’s this a record of?

The cropping, to me, seems to suggest a film strip – they add a temporal element but refute that (we look for changes but the image isn’t ‘animated’) its like the image is somehow stuck in this ‘in between’ part of a frame, was the ‘temporal’ something that interested you?

Ha, no, I never thought it about like that. I can see what you mean though. Well, there is no movement here in the sense that the only thing that either edge segues into is… the other edge! The image only loops onto itself. Could it be seen rather as pointing to the claustrophobic feeling of being stuck in a dysfunctional relationship?

What are your future plans, upcoming exhibitions etc?

I now have representation in New York with Denny Gallery, since last spring, and they are showing some of my recent work in Miami Beach this week, at the UNTITLED. fair. And then it’s just over a month before my first solo exhibition at the gallery, which is titled Indeterminate Objects and will run Jan 30 – Mar 9. It will focus on my sculptural work. Funnily enough, Jonny Briggs will be having a show at around the same time only a few blocks away! But I’m currently in an itinerant phase, which impacts on my ability to work in 3D, so at the moment it’s back to images. I’m doing something that I’ve been thinking about for a while involving found mobile pictures, tentatively called Non Sequitur. It’s all in the editing though – I have in the region of 800 images to filter and sequence – and that will take some time. Beyond that, who knows. I can share one as a little safe-for-work preview. Editing is a non-issue with one!