Jasmine Johnson’s work often centres around individuals. Somewhere between documentary and portraiture, her videos, sculptures and installations access the universal through the guise of the singular. In responding to her Project Space commission Upright, I have tried to follow her own framework, presenting the narrative of a life through fragments and record, and juxtaposing projected responses with that which emerges from human action itself.

Solo

Humans started recording animals at the same moment they began killing them. Although there was surely no comprehensive understanding of ‘extinction’ in the minds of men 20,000 years ago, there is an evident correlation between the need to record and the deliberate cessation of existence. It is a uniquely human condition to simultaneously wipe something from the face of the earth, and be fascinated by its potential worldly significance.

Extinction supposedly happens in a moment – the moment the last individual of a species dies. Although, the capacity for recovery is lost long before this point. Because of the difficulty of determining the exact moment of extinction, it is usually declared retrospectively. This declaration is dependent on a totality of human knowledge – of remaining animals, locations, distances, potential encounters, surrounding environments, predicted threats, changes in conditions and the territory of poachers. Sometimes the declaration is wrong. Sometimes species resurface.

Exploration is empirical. Many animals and objects were collected because of the belief they would soon be lost, and that universal loss could be overcome by imposing a singular loss. This anxiety, and/or recklessness, caused by the human desire not to ‘lose’ something, becomes an irredeemable, perpetual cycle, rooted in collections, museums, objects and archives.

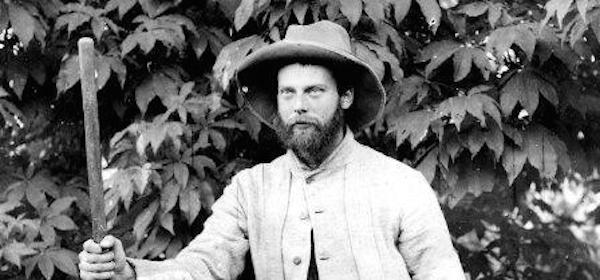

Over the course of 45 years, Major Percy Powell-Cotton embarked on over 28 expeditions across Africa and Asia. His subsequent collection consists of almost 2,000 specimens, including animals which are now greatly endangered: the Ethiopian Wolf, the Angolan Giant Sable and the White Rhino. Alongside primate material, Powell-Cotton kept extensive records, affording each animal a map reference, detailed body dimensions, an age, a sex and external pathology with local names for diseases.

Activity

‘An ideal white man’s country’

‘Our head man, who, as usual, had gone on to prospect the route for the coming day, did not return that evening, nor the following morning, but we found him at the next camping place near the foot of the Marmanet hills. This was a lovely bit of country ; its clear streams, undulating grassy hills, fine clumps of trees and patches of bush, reminded one of an English park. Of the many ideal spots for white settlers which we had seen, this was one of the finest, lying as it does at an elevation of over 6,000 feet. It is well watered, and the little woods and copses scattered about the hill-sides and in the valleys would provide timber and firewood. According to our Masai guide the rich pasturage clothing the valleys is always good, and as the railway is within easy distance, there would be no great difficulty in getting both stock and produce down to it. Being at present a “no-man’s land” there are no natives to be dispossessed or to feel aggrieved at its occupation by white men.’

‘Mild-mannered crocodiles’

‘Baker took C— out in a collapsible boat, a relic of one of Lord Delamere’s trips. They managed to get close to a hippo and stepped overboard, so as to fire a steady shot, but the water proved a little too deep for C—, and in his endeavours to keep his footing in the mud, he missed the quarry.

As they could not scramble back into their unsteady craft, they had to walk ashore, and on the way C— stepped on a crocodile, which skinned his shin as it wriggled peaceably aside. The crocodiles of Lake Baringo seemed to be much more mild-mannered than any I had previously met with either in Africa or Asia. Perhaps this is due to the enormous number of fish with which the Lake is stocked. At all events, the cattle and sheep which graze on this shore of the Lake are but seldom molested, and I could only hear of two cases of men being attacked, one of which, curiously enough, occurred just before we arrived at the boma.’

Mounted crocodile:

Accession number: HC.2013.114

Mounted taxidermy crocodile, with teeth and claws, in crawling position, with mouth slightly open. Mounted onto Perspex panel.

Number of objects: 1

Dimensions: L = 1040mm W = 260mm H = 140mm

Materials: Reptile Skin

Processes: Stuffed

Keywords: Reptile Part

Classes: Specimen

‘I stalk ostrich and walk into rhino’

‘On the second morning, I spotted two ostriches in the distance, and as these birds are quite the cutest I know, I left my gun-bearer behind, and started for them alone, armed with my .256.

As I was edging towards a thick belt of scrub, two big ears, twitching among the grass not twenty paces away, attracted my attention, and for a moment I thought it was a zebra lying down. A peep through my glasses, however, soon showed that it was a big rhino; luckily its head was away from me and the wind was fair. I turned and beat a hasty, but noiseless, retreat to the nearest bush, behind which I crouched, for taking on a tough old rhino at close quarters with tiny split bullets, which were all I had with me, was hardly in my programme. The brute, however, had heard me, and scrambled to his feet, turning his great head from side to side, his ears cocked, and his wicked little eyes peering about trying to spot the disturber. I lay quiet till he gave up the search and began to feed straight towards me. Now a rhino in that country, when he discovers danger close at hand, invariably makes for it, so I decided on aggressive tactics, and sitting up, got the sight to bear on the back of his beck, and fired.

Off he went well to my right front, but as he got abreast of me, either catching my wind or seeing me, he wheeled around and bore down in my direction. The next cartridge missed fire. Throwing out the empty case, I plugged in two bullets as quickly as I could work the bolt, which made him swerve across my front at fifteen paces distance.

I let him have another as he passed me, and one at his stern as an au revoir; then I breathed again.’

Skull, rhinoceros

Accession number: HC.2013.1

Skull of a rhinoceros, both cranium and mandible present.

Number of objects: 2

Dimensions: H = 410mm W = 280mm D = 550mm

Condition: Good

Materials: Animal Bone

Classes: Specimen

Duet

A taxidermy animal is definitively irreplaceable. From being part of a community, it becomes a singular, archetype of its species. It is representative. Taxidermy animals are artworks, cultural objects, scientific specimens, museological wonders and symbols of contemporary environmental anxiety. Their death affords them a symbolic status. A status which is inescapably generated, facilitated and maintained by human beings.

In October 1906, while on an expedition in Uganda (and on his honeymoon), Percy Powell-Cotton was attacked by a lion.

The camp in which his group was staying was populated by lions. At nighttime, they would circle and play around the camp, but would always disappear before daybreak. One morning Powell-Cotton saw a large, solitary male slowly making his way back into the jungle. The explorer fired and badly injured the creature; it retreated into the foliage, hiding itself almost entirely. After an hour and a half, Powell-Cotton approached the lion, assuming it severely injured. Instead, the lion charged. Powell-Cotton fired his gun, breaking the lion’s jaw bone. The animal clawed at his coat, and attempted to tear open his abdomen. A copy of the magazine ‘Punch’ stopped the lion penetrating flesh immediately. While Powell-Cotton lay underneath the animal, it was attacked with a whip and shot dead by two of his group.

This incident, as a paradigm of 20th century male adventurist exploits, attracted a lot of attention. ‘Punch’ magazine commemorated it with a short poem:

‘The wounded lion with a lusty roar

Advanced to drink the gallant Major’s gore;

But suffered great confusion when he felt

An unexpected ‘Punch’ below the belt.

Sportsmen ! herin I find a happy omen

Good for the deadly need of your abdomen.

Would you defy the foe upon his treks

Wear ‘Punch’ for armour, ‘Punch’ for aes triplex’

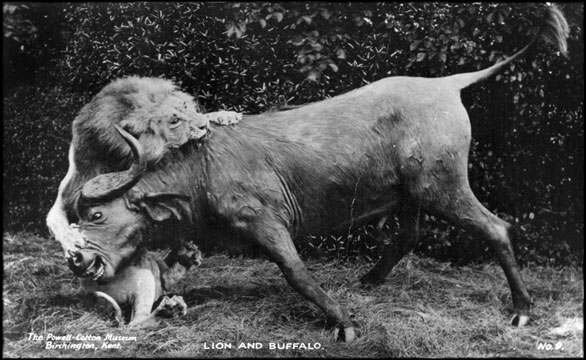

The lion was returned to Powell-Cotton’s estate where it was stuffed and mounted by taxidermist Rowland Ward. Placed in a diorama with a Semliki red buffalo, the animal has been crystallised in battle for over 100 years. The lion’s claws are dug deep into the buffalo’s muzzle, pulling it towards him; the scene is weighted towards the lion’s mouth. Although it is a battle in progress, the fate of the buffalo is unmistakeable.

In Powell-Cotton’s diorama the lion wins. Or, is in a constant state of winning. The scene pays homage to the ruthless and supposedly unbeatable animal, while also celebrating its death. Powell-Cotton’s ripped suit is displayed alongside it, afforded the same historical value through the conventions of display, creating a hierarchy of victory. It is a constructed natural history. A construction reserved solely for the upright.

Extracts taken from In Unknown Africa: A Narrative of Twenty Months Travel and Sport in Unknown Lands and Among New Tribes, Major P.H.G. Powell-Cotton, first published in 1904 by Hurst & Blackett Limited, London