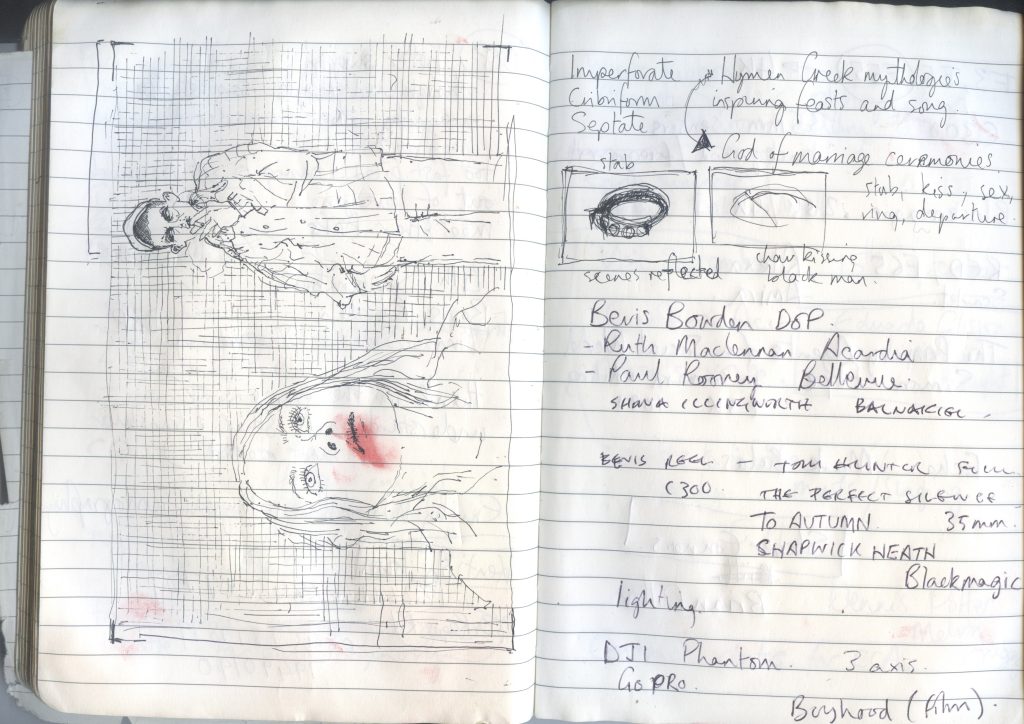

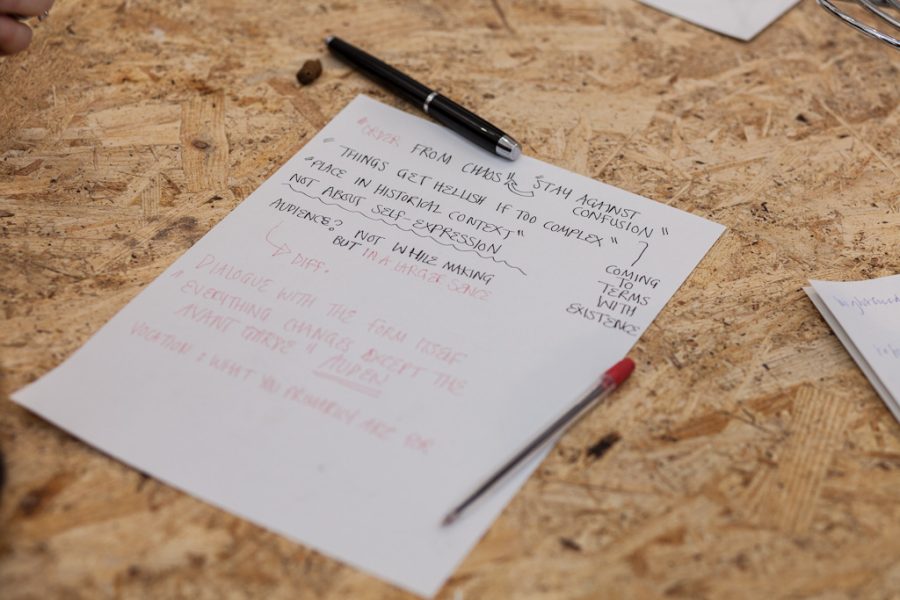

It’s easy to be seduced by the ink stains and the violent erasures. It’s easy to see in these crossings out, in the artist’s frantic scrawl, traces of the artist’s body. What lies beneath. Evidence of the life, proof of the blood in scanned units. I’m not interested in binding them, protecting them, as in The Diaries of Franz Kafka. I don’t want to romanticize the mess of the notebook or fall for its viscerality, however much I enjoy the ride of the broken syntax. Finding the words through arrows and loopholes. Zig-zagging through ‘multiple narratives’ and ‘too much to take’ and ‘sexuality/pathogens’, appearing as if a visual poem, but in fact a method of writing and research. Note-taking contemporaneous with thinking, faster than the clock. Copying from Archives of Sexual Behaviour Vol. 31 and making your own in acts of guilty trespass.

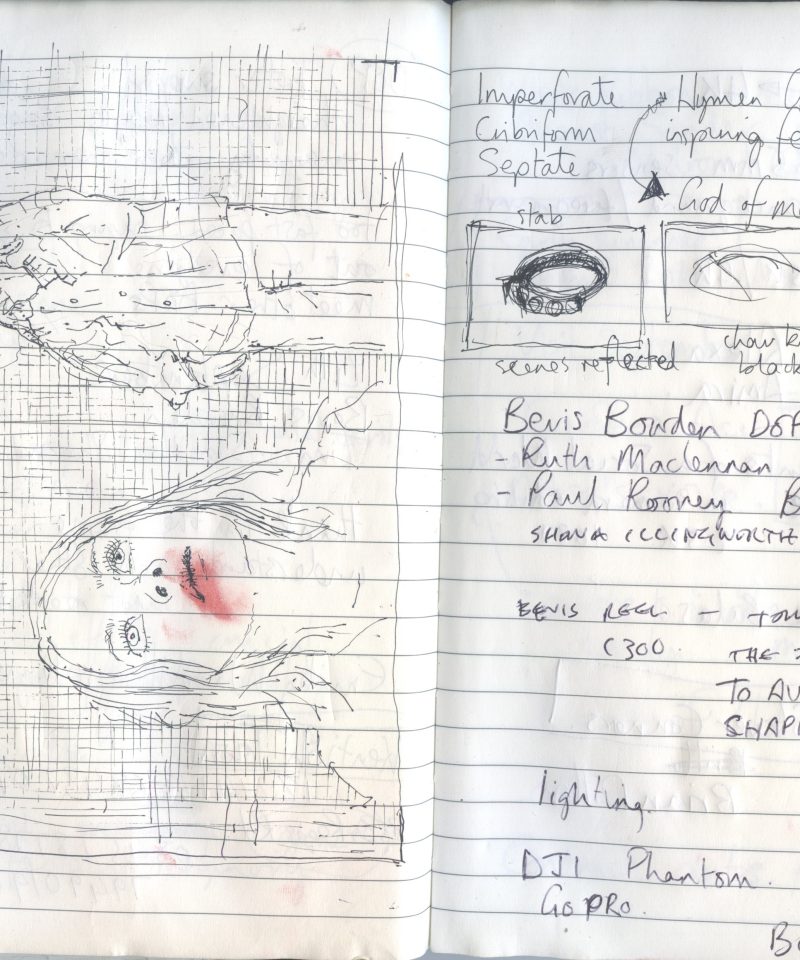

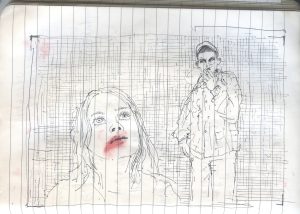

- Going back to the notebook. It’s called sketchbook but there’s more writing than drawing (aside from the wide-eyed girl with a red-stained mouth). She’s sketching her thoughts and having fun with word play. From ‘hymenologies’ to ‘Hi Men’. And later: ‘Film takes on blood as currency / Nose as virgin Nose = virgin.’ Reading these fragments, I remember Isak Dinesen’s story ‘The Blank Page’, in which the bloodied flax of formerly virgin brides is displayed for public consumption. One anonymous princess exhibits a sheet of ‘snow-white blankness’, withholding her body in act of radical resistance, owning the page as M does her notebook. Blood moves and mutates through the turning of each scanned page, in numbered narratives and feminist concepts about men being hot and dry and women being cold and moist. Order and health versus disorder and illness. Meanwhile, the author and artist asks herself to do things and buy the best value equipment, the backstage clutter and correspondence. She writes down questions for Isabel and nose surgeons, as well as phone numbers and emails, so to talk to people who might help; she talks to herself, too, not as a means of confession, but as a means of making. Of seeing things happen. Unfold. This is starred, hence important: ‘ *build up of blood causes girls to become delirious, violent, even strange themselves’, which I can relate to as I write more text from stuff, libidinal and automated, building layer upon layer – as in the chaotic and cluttered syntax of the notebook.

I knew I was interested in experiencing Blood in ephemera when I asked Marianna to dig out some stuff for me a few weeks ago, but I was still unsure of how I might use it. It was titled FOR ALICE, transferring its responsibility and desire through the click of a send. I’ve been circling the works and the artists for a while now, writing letters and emails to them, building an archive of intimate texts in the margins of the internet. Through the stuff of language exposed we are very nearly touching, if not physically, then maybe materially, as Berlant says: ‘In an intimate public sphere emotional contact, of a sort, is made.’ I am drawn to this writing of embodied hesitation.

Some of our correspondence will stay public, performed in text, but some things said will remain invisible, languishing in the bottom end of the inbox. Or the back pages of the notebook… It might find its way out in time, but time will be different by then.

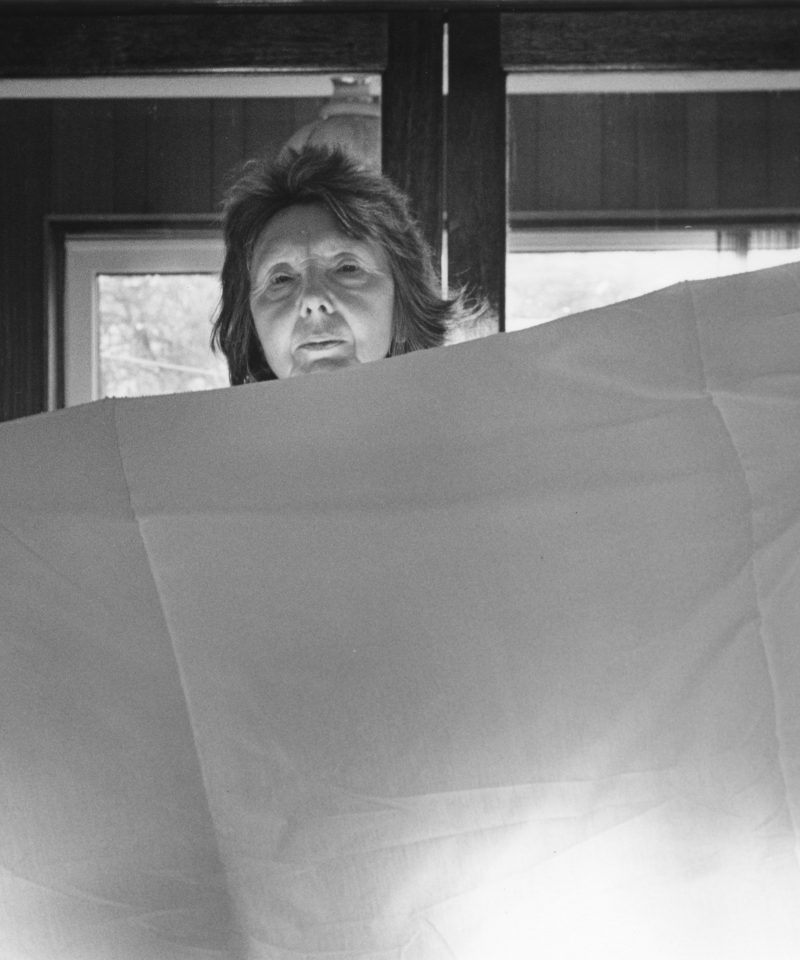

- An arm (could be left or right) is outstretched as in ‘The Willful Child’, cropped as a colour image with no defining hand. Or thumb-prints to investigate. But it is scratched and pink and sore, with lines appearing as bloody inscriptions. Her flesh is shot with blue, like a fabric woven with two threads. Those veins look difficult to manage, probably made worse by the Albanian winter. I wonder whose limb this belongs to. Marianna’s, Lali’s or Isabel’s? Does the sick child of the story also self-harm? Inject heroine into her blue threads? Anna Kavan died this way. I turn to her Asylum Piece, in which she territorialised her own (institutionalised) illness in writing: ‘It seems ages since I have been able to concentrate on my work: and yet I am obliged to put in the same number of hours each day at my desk.’ (The ill in willfulness.) I later learn that this image called ‘PROCESS’ is evidence of Marianna’s cut-up arm: when nose-building goes wrong. I stumble across two consecutive images of the nose and find pleasure in these x-ray view-points: from the wooden, chicken-wired construction, stripped back and naked, to the newspaper layer that coats it. I imagine M climbing all over it, screaming at the sharp edges of its skeleton. In physical pain. But also because it’s her film. And because she can.

The archive is a space of affective attachment and contact, of getting closer to the object and oneself (often through the pencil markings you make). Through making more stuff. It’s a resource but also a partner, a companion, and a friend. (It’s basically Lali.) In the time between the email I sent requesting ephemera and the time and space of writing this post, I’ve moved a bit in my thinking, worked out that the archive I am getting to know is less the archive of secure institutionalised masculinity, and more the floating archive, the one you might ask for but the one you can’t predict. Or value. I am less interested in discovering context and biographical detail, as imagining narrative and desiring the marginal object, away from the exhibited final thing. My inquiry is formed by intimacy: the unfinished, the open, the leaking. Bodily forensics without the proper tools, forgetting the protocol:

Calling to mind José Esteban Munoz in ‘Ephemera as Evidence’: ‘Queer acts… contest and rewrite the protocols of critical writing …’

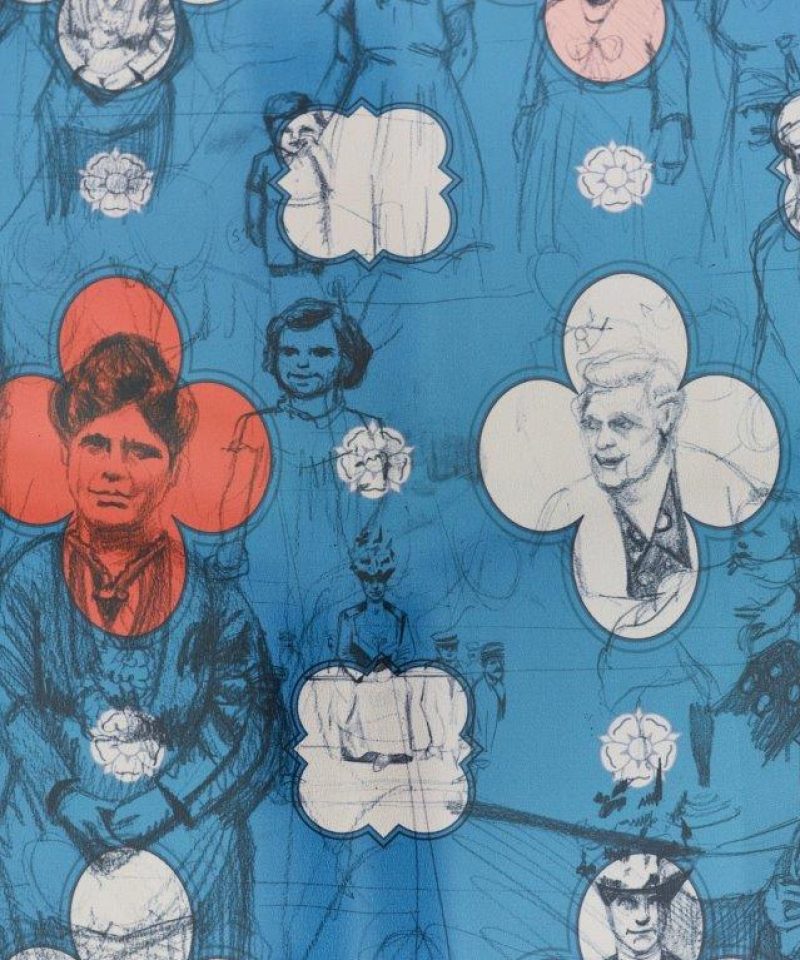

- Staying with photographs, or a photograph of photographs. This one has been mediated and compartmentalised, perhaps to make it easier to compare the sworn virgins’ faces – their immediate exteriority. I know Lali, or at least I feel like I do (she’s got her thumbs up in another photo); and I’ve met Drande before in a video. She’s bottom right. I feel bad for thoughts surrounding who looks more masculine, as if the reproduction of a ‘male’ aesthetic is the only cause or reason of their passing. That said, Lali has a naval hat on and is smoking, by the sea, not in the mountains. She is beautiful and beguiling, not as man or woman, but as both or either. This must be one of her’s and Marianna’s first meetings: the interview research. I don’t have the audio so can only guess at their conversations, words and phrases that probably found their way into the script, reframed and chopped up. All of their faces are smooth, but some are more lined than others. Only the second virgin is showing her teeth, a smile of understanding and warmth. Contact. There was a character to fulfill for the purpose of Blood the fiction, but the life extends beyond the frame.

Ephemeral objects embody the traces of the performance and are in this sense, objects of performance, too. Time-based and durational is this material waste, but it is also the wayward document constantly performing itself, mediated through the scanned selection process. I want to extend the fiction, create an assemblage of bloody stuff. I want to write in and out of the ephemera, and get close to it, not in order to prove something about the work but in order to inhabit it and desire it and imagine it and perform it. In language. To provide the work with a queer life outside the gallery walls.

- Isabel sits on a green chair in front of Marianna and her camera. She is Goldilocks. She wears a white vest and grapples with the script in her fingers, crosses her legs, makes only occasional contact with her interviewer. Spurred on she says, repeating my same confusion:

From some angles she looks like a woman and from some man. It’s quite weird that she’s devoted her life but I can see why…

M responds: Can you tell me?

Men get more advantages and more freedom than women who like clean and cook. Women are basically their slaves, basically…

The language of the young girl is, like, reoriented in the texture of the script… resulting in a fictional Isabel that, through Lali, and through hysteria, and through a red bleeding body, challenges the stable foundations of femininity. Precariously balanced on the ‘wobbly chair of heterosexuality’, this is Dodie Bellamy writing of her own Goldilocks Syndrome, unearthing its sickened potential:

‘Rather than identity, we uncover a void, a vacuum, an inrush of sticky desiring others – a non-position where the unbridled power of the libidinal child can be unleashed, the child who can blow up the world with her thoughts, the child whose body gets blown up over and over again, each time resembling in ways that get stranger and stranger, the child that people back away from, otherness blazing from her, a molten orange and red aura. When this child enters the discourse of heternormativity language is going to fry.’

The blazing young girl: dangerously red in her otherness.

When Munoz wrote about looking at an image of a Tony Just performance, and found that ‘a few people recognized the image as that of a toilet bowl, many saw it as a breast, some only as a nipple, others as an anus and still others as a belly button’ he also opened up the indeterminate and desiring potential of ephemera. It desires us and we desire it back. It’s mutual; this performative relationship of dislocated time. The ephemeral object is bound to the temporal moment in which it was spawned, but it also rejects it. Tagged by time it likewise travels, down into wonder – where feeling and writing merge.

- Getting lost in the nose. A kind of building with separate rooms and levels, its insides painted pink. Raw. In through the anterior and out through the uvula, making my way through the inferior, middle and superior turbinates. Imagining I was Isabel. Running through viscera and excess. The anatomical drawing of holes and vestibules and winding passages sums up the experience of hallucination: ‘STORYTELLING’. Marianna’s own graphite drawings of vivisected noses follow the science. No bottom lips are drawn in these androgynous shapes, only the nose and cupids bow. The final nose is lined and withered, her lips indented by the daily drag of a cigarette. The scanned image is untitled and un-named: I wonder if it is Lali, re-drawn… (a good guess, I later discover).

This is Kathleen Stewart writing of the fluid (sometimes perverse) way we experience everyday objects: ‘From the perspective of Ordinary Affects, thought is patchy and material. It does not find magical closure or even seek it, perhaps only because it’s too busy just trying to imagine what’s going on.’

Accidents happen here, in this space beyond the frame,

as the stuff of making finds a new frame in writing:

In this, my postscript to the intimate archive, I have tried to imagine what’s going on in the archive of Blood. Write as I find it. Pay it a different kind of attention. We might recognize it and its people; we might not, the stuff of this bloody catalogue, or notebook.

- A scrappy ring bound notebook for a diary, a vessel of documentation and of fiction. The writing moves in and out of description as this resilient, sleepless writer (‘Yesterday, I mean this morning, I left home at 1:30 am to catch three nightbuses to Heathrow) hones in on the everyday details. Latte macchiatos can last for as long as you will them to, as the act of waiting is then trapped in the act of writing. M (I think it’s M) is sitting in a café, like the protagonist in Marguerite Duras’s Moderato Cantabile. The French novelist is also scribbled in M’s notebook, along with other reference points like Angela Carter and The Company of Wolves. Also: Antonia Young; Balkan Peace Project; Mike Kelley. The first person dominates this diary form. Of course it does. It’s the language of the young girl, older than the first, but still candid and confessional. We think we can see her, but the page is dislocated from the narrative, like a cut-off arm.

We cannot see the whole of her.

Blood by Marianna Simnett was commissioned as part of the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’. The Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me’ are a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and FVU in association with CCA, Glasgow and University of East London, School of Arts and Digital Industries. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.