Anne Haaning, KhoiSan Medicine (excerpt) 2014

Anne Haaning is one of the four artists participating in the Jerwood/Film and Video Umbrella Awards: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ (#WWTSOM?) exhibition, the first stage of a major awards-giving process for moving-image artists in the first five years of their practice, a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and Film and Video Umbrella. In the following interview I asked her about her new work KhoiSan Medicine (2014) in which she analyses digital culture through a wide historical lens and a reading of the mythologies of the ancient KhoiSan people.

What is KhoiSan Medicine?

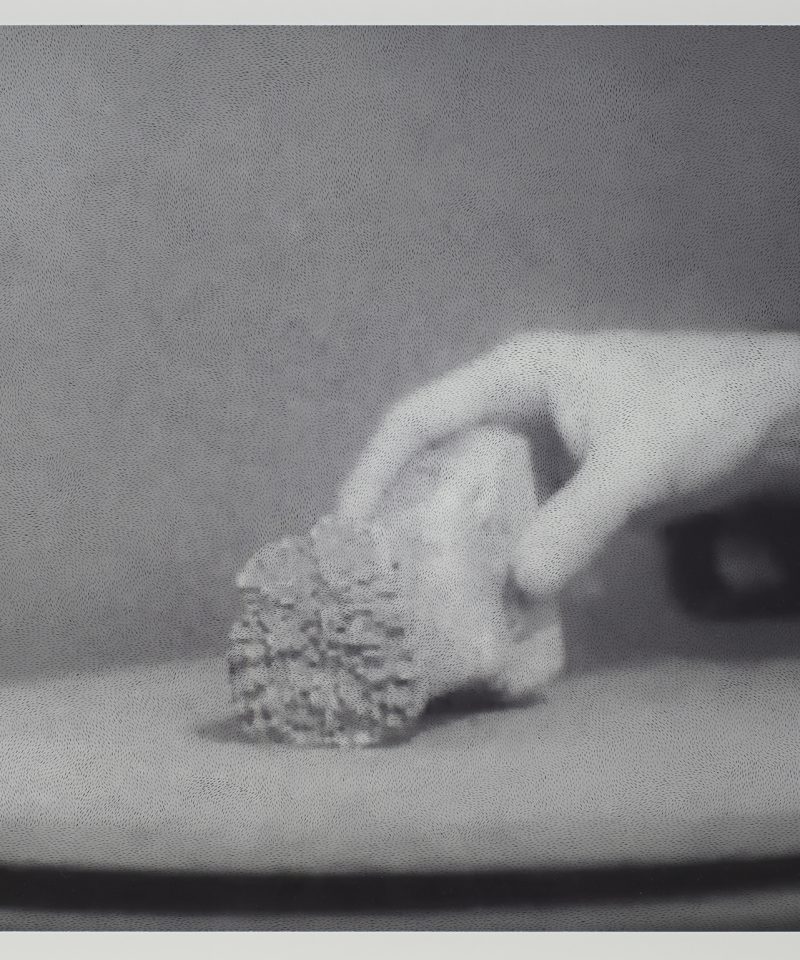

My starting point for making this work revolves around hunter gatherer myth. I’ve tried to approach the age I live in (and particularly the digital) from the same distance an archeologist would when trying to unpick lives and identities of humans thousands and thousands of years ago. The KhoiSan are a people descended from the first human beings to arrive in a desert (in what is now called South Africa) more than 100,000 years ago. I’ve been to that desert; it’s an extraordinary place, in a sort of subtle way. At first glance the most impressive part about it is the vastness of it, it’s not like the picturesque screen saver sand dunes at all, it’s just rocks and bushes for miles. What makes it so special is its unique geology; the ground there has been dry for hundreds of thousands of years which meant that there was barely any erosion of the soil, and for this reason stone tools from different generations and human species divided by millennia lie next to each other in the same field. In theory you can access all of human history just by sifting through the sand with your hands. For me this really recalls what is happening with the digital and the internet, not so much the access to everything but more the levelling out of time. The ‘shallowness’ and the ‘flatness’ (and I don’t mean this in a derisory sense) (I’m tempted to make the reference you’re making! “It is the flattest and the dullest parts that in the end have the most life.”)

The palaeolithic anthropologist Chris Low is an expert in KhoiSan peoples and their relationship to myth and wind; he was, clearly, influential in the course that the work took. One of the voices in the video is Chris Low’s’, it’s taken from a lecture he did on Potency and the Role of the Environment in KhoiSan medicine.

So finally, to answer your question. KhoiSan Medicine is a direct hint to where the work is coming from but also, I hope, a title that encapsulates ‘it’ – the video, as a substance: KhoiSan medicine; a drug that possibly intoxicates, heals or enlightens.

Is it a theme you’ve addressed in your work before?

I’ve been trying to dissect the digital for a while, but it’s the first time I’ve taken such a ‘profound’ stab at it. I got really fed up with talking about ‘the digital’ as ‘other than real’ – the thing that separates us from the world. For me the problem with the digital is the force that drives it (military, state and capital) and I guess I’m kind of going down a route where in theory I’m fighting for ‘digital rights’, the digital itself is just another emerging media, like the printing press was when Bibles were the only books to be printed. This work is the beginning of what I think will be a longer commitment to the digital as an ecology in its own right to be understood as an extension of the physical, rather than a removed data field.

I picked up on a comparison between the immaterial image and ghosts, or spectral digital identities – is this reading as you intended?

Yes. This sort of links back to my interest in myth. One of the reasons I’m interested in applying the idea of myth to the digital comes from their shared immateriality. In contemporary western society, matter generally takes precedence over the immaterial, hence the internet being some kind of ‘virtual’ reality. For the KhoiSan people, traditionally there was no division between mind and body, space and time and even dead and living – a worldview that, to me, both prefigures and recalls the digital. In the digital, history is always now or uncertain. The end is transitional, and so what we leave behind of digital evidence of our existence is indeterminate. ‘Ghost’ translated into Danish is ‘genfærd’ which translated directly means gen = re and færd = journey. I like that definition of a ghost. The journey that repeats.

How did you make the imagery for the video – was it all done within the screen (ie. through graphics and found material) or did you film anything yourself (using a camera)?

I usually pick up certain elements (video and sound) that anchor with the main idea. I then translate those elements through a number of editing tools, I guess to see what happens when those translations are compared and how meanings are linked to their mode of representation. It usually involves filming, making 2D and 3D animation, and processing found material. Eventually those elements start connecting, sometimes they don’t and then they have to go. Making KhoiSan Medicine was a very different process from what I usually do in that I was lucky to get the opportunity to work in the studio of UEL (University of East London) which both meant I could be a bit more ambitious with what images I could achieve but also that I had to plan everything out beforehand. It was terrifying, but it really paid off, I think. Also, it was great to let other people into the work during the shoot, and see this otherwise extremely intimate process from the outside suddenly.

I’m interested in whether you’ve worked with celluloid film before? If so, how did you find the difference in quality of experience or filmmaking?

Briefly many years ago, but never professionally. The materiality and the presence of it fascinates me, and particularly the idea that the images are actually evidence of a place in time, but my way into film making was actually through architecture (I graduated from the Royal Academy of Architecture in Copenhagen in 2004), so my first experience of it was through making stop motion animation exploring temporality in architecture. In that way, I think my videos are made as animations even when they include shot footage; I understand the duration through frames rather than seconds. Also, the way I used video in relation to architecture was often to do with proposing a world that didn’t exist yet, so my relationship with video really hinges on its precarious relationship with depicting the world as it is.

Whose are the voices we hear? Are they reading from a script?

There are three voices, one is Chris Low as I mentioned before and the other two are motion graphics experts presenting the latest plugins and advances in the motion graphics industry. I’ve watched thousands of youtube tutorials, this is how I’ve learnt everything I know about 3D animation and motion graphics. So I know that language very well, and I’ve been struck by how often terms from the digital universe of the programs refer back to the physical world, and how these conversations taken out of context suddenly start to say quite strangely profound things about the physical world. In the original source material, one of the digital experts is presenting a plug-in that you use to make particles. This means making fluids, clouds, dust, sand… etc. anything that moves according to swarm-based dynamics, and I thought that was the perfect counter part to my fascination of the mythical ideas of wind and flow.

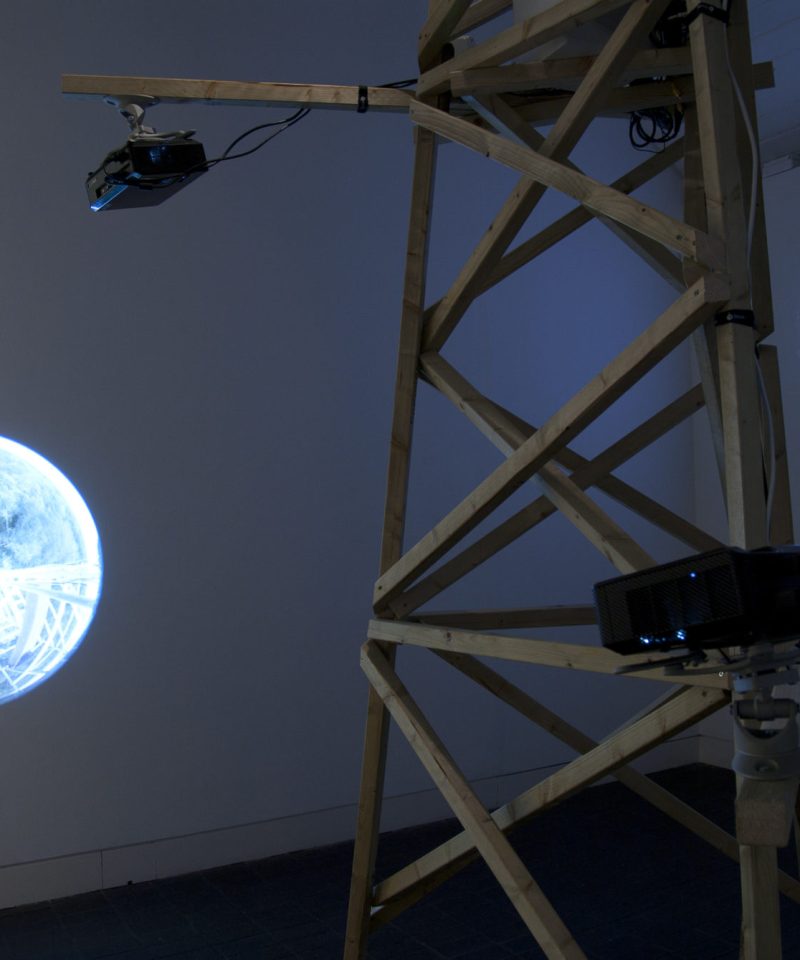

It’s interesting how you use the wide-format screen to mirror the space in front of the screen. Did you have an idea of how the viewer would encounter the film (using the two sets of headphones hanging from the ceiling) before you started, or did it come to you later in the process?

Having the headphones in the space as a mirror of the video was something I decided quite early on. Practically, the decision of choosing headphones rather than speakers was a response to a logistical constraint. We are four artists in two rooms. And in the end I think this constraint was very helpful in driving the work. Having the headphones there as a mirror is a way of implicating the audience in the work and of extending the video into the space of the gallery. With youtube and vimeo being the primary platform for watching videos today, I think it’s important to emphasise the unique situation of actually watching this thing in a room, and that this is where this particular video works and belongs. I also like the way the hanging headphones stage the viewers wearing them, as being weirdly attached to the work with this pseudo umbilical chord. As for the wide-screen format, I knew from the beginning that there was going to be a lot of flow in it, and so it seemed suitable with a very wide and horizontal space for this to happen.

The headphones seem to be an extension of the flow depicted in the film. But I’m curious about the two ‘dead heads’ pictured next to the head we see doing what we’re doing: They’re very cinematic! Has their wind expired? What do you mean when you say (in the notes accompanying the film) that digital bodies can have a more lasting presence than bodies?

In this constellation it’s clear which of the three is ‘the original’, but really, they’re all copies. As you say two of them are ‘dead heads’, but all three heads are doing exactly the same and are ‘made of’ exactly the same immaterial stuff; the only important difference is that two of them aren’t staring back at us. I suppose they are a bit further down the digital chain of transition. Their non-existent gaze kind of reminds me of the feeling I get when faced with ancient greek marble sculptures. They’re oblivious to the world, how ever much it’s changed and even when they lose their limbs. I think the same goes for the digital.

KhoiSan Machine by Anne Haaning, alongside the three other new works in the Jerwood/Film and Video Umbrella Awards: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ exhibition is on show at Jerwood Space, London until 27 April 2014. The exhibition will also be installed concurrently at CCA: Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow between 4 – 21 April 2014.