Transcript of an email interview with Lucy Clout

A: From Our Own Correspondent continues your previous investigations into ephemeral forms of speech: can you explain your interest in the interview as a mode of verbal exchange?

L: I listen to a lot of podcasts in my studio; particularly interview podcasts, of which there are many. It’s a quick and cheap way for them to make content. Interviews such as these are not hugely edited, and are often much longer than would be typical of more traditional media platforms. They offer me the comforting background witter I’ve talked about in previous videos. In From Our Own Correspondent the journalistic interview is used as a model of professionalised conversation and exchange, one that is potentially full of hierarchy and flattery; the skilled formation of intimacy and formality, and the drawing out of people and directness. In the beginning of making From Our Own Correspondent I was thinking about those podcasts, of producing, essentially, your own chat-show: I was thinking about the difference between asking a question where you know what you want the other person to say, and asking a question where you need the other person to bring something you can’t provide. Of course, these aren’t separate situations, but things that might play out within a single interview in which the power dynamic ebbs and flows. In my work, which began as a performance practice, I have long been interested in the exchange between performer and audience. During an interview (a certain type of interview at least) the interviewer and subject can play both the roles of performer and audience at various times within the exchange. Much of what I wanted from the journalists I spoke to was to perform themselves: that is, as women with jobs, as professional people who are rather protective of their professionalism and who are expert at understanding what is at stake when you speak publicly.

A: The Internet is seen as the arena of confession, and in much the same way the interview is obsessed with exposure, but both seem to be as much about disguise and performance as truth…

L: Absolutely. Confession, intimacy, shame and visibility are all important in the work. The confessional, the biographic, and particularly the ambiguously fictionalised memoir, seem to be having a moment in the work of writers like Chris Kraus, Eleana Ferranti and Karl Ove Knausgaard. There is a question at the heart of the video about the need and desire for contact with another, and also with what that contact might supply you with and how. Online spaces also demonstrate how confession can exist without needing to relate it to a whole person or a whole truth – as a type of rhetoric. This exists against the backdrop of intermingled professional and personal lives. In a way the pleasure of online sex is that it offers relief that can be compartmentalized, that it does not disturb one’s whole life (except when it does). It seems like it is a public act when in fact it is mainly very private. In the last third of the work an unseen person re-posts, retroactively, the banal and shame-filled conversations of a disgraced politician, which the avatar is puzzled by and drawn to. She enjoys the emotions surrounding confession and shame, providing a witness to the original act of re-posting, in turn activating that unseen person’s feelings and desires. In From Our Own Correspondent, I was interested in the idea of a ‘story’ as a set of events that can be separated out neatly, in order to be presented. There is the final monologue; there are the five women edited together to create an authoritative voice; there is the avatar. It’s very much a video about being, and not being, intertwined with others, about the ways in which the performance of various professional and personal roles blend into one another, both online and psychically.

A: I am also interested in the way you perform your subject matter, as you interview the interviewers, and make them interviewees…

L: It reiterates that documentary trope when the film acknowledges the maker in order to acknowledge the subjective process of the making. From Our Own Correspondent is not an objective work: it addresses the wants and loneliness of a not hugely realistic avatar. And so, the journalists were so suspicious of me. I mean, of course they were: they are people who have thought more than most about their visibility in their work; about posterity, and about what might be given away as an interview subject. I am a bad interviewer, in contrast. There is a moment in the film when I am told off for all the nodding reassurances I keep doing. At other points they tell me to ‘relax’, to ‘try asking the question again’, or ‘ask it like we were sitting at a bar together’. My amateurism allows those particular exchanges to happen; except, of course, I am not exactly an amateur. One of the reasons the journalists were so puzzled by me was that I was describing the interviews as my job.

A: What does the avatar symbolize for you and what are the sources behind her construction?

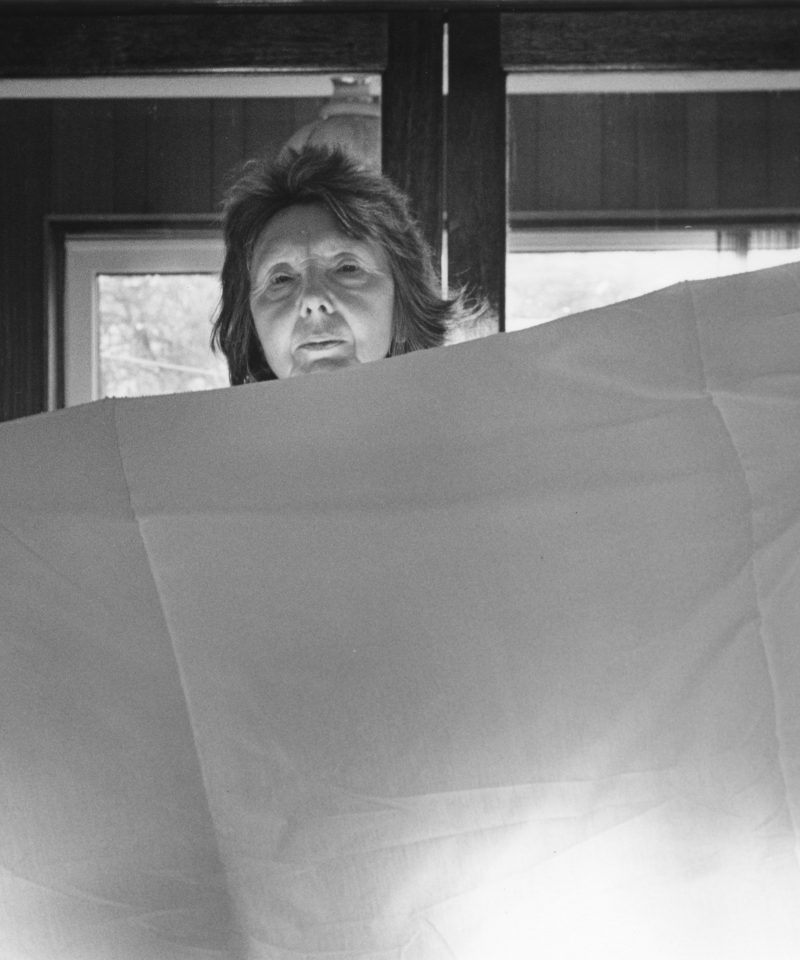

L: She is a maker; she is a worker. She is an example. She is also just a woman in her 30s with a job. Designing her look involved trawling the pages of the Next catalogue (it still exists as a physical object it turns out!) and searching ‘professional work wear woman’ online. There is something of the Holly Hunter in the film Broadcast News (1987) in her hair. She is older and fatter than the original version, and that scaling was tricky: the gusset was scaled particularly poorly at first. She wears these knickers of an almost towelling texture. I had in mind a type of foamy material that is used to make cheap everyday seamless underwear dense and absorbent. She has taken her skirt off in order that it doesn’t crease, or maybe she hadn’t put it on yet, signalling a half-readiness to perform. She is both rehearsing alone and running over her day, performing a looping type of stasis within the hotel room.

A: What is the significance of the hotel room in the context of the work?

L: The hotel straddles domestic-space and workspace. It also offers the work a particular flat tone that means the empty hotel room can be read as a still or CGI. The potential for pleasure and horror is abundant in those spaces. Checking into a hotel alone I always have a ghoulish wonder if this is where I am going to kill myself. As well as suicide, hotels are a place for honeymoons and meetings and good sex and luxury and presentation writing over a slow Internet connection. Mainly, of course, nothing happens.

A: I was wondering if you could talk about the relationship between the ‘work’ of the interview and the ‘play’ of the correspondence and pop up messages that flash across the screen? Is it something to do with a breakdown in public and private spaces?

L: I was really thinking about anxiety and work and self-soothing. There is something in there about the breakdown between work and non-work time; about the vigilance that is felt to be required to protect a professional persona, and the psychic toll of that. Which of course means that spending time on hook-up sites makes perfect sense: what is masturbation but anxiety, attractive risk and self-soothing? Did you read about those judges who all got disbarred recently for looking at porn on their work computers (but not while they were actually in a trial)? My woman is not working all the time: she is looking for someone to message; she has time to fill and an empty hotel room that might be full of promise. She just needs someone else to activate it.

From Our Own Correspondent’ by Lucy Clout was commissioned as part of the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’. The Jerwood/FVU Awards 2015: ‘What Will They See of Me?’ are a collaboration between Jerwood Charitable Foundation and Film and Video Umbrella (FVU) in association with CCA, Glasgow and University of East London, School of Arts and Digital Industries. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.