The sound I think it makes is, is that whispering sound, to me it sounds, it almost sounds, um, uh, what’s the word I’m thinking? Um, like historic, not historic, but, um, oh: a legend, it, it sounds like a legend, you know, when you think of a legend or something way back in the past you get that, that, it sounds like that to me, like this legend or somebody’s, this whispering sound: it’s a legend.

Hannah Rickards

**

I’m sitting in what feels like a dark, warm box. There’s no one else in it, and I’ve sunk into the ground on a beanbag. A loudspeaker stands in each corner of this box, or den, and ahead is a monitor through which Chris Watson’s voice is walking me down a Kielder forest path. The trees are dark. We come to a little stone bridge, and Watson’s voice dissolves away, the monitor fades to black, and the space plunges into darkness.

**

I went home and started reading about ravens. I came across a photograph of them roosting on an abandoned US Nike radar dome. I read Edgar Allen Poe’s magnificent narrative poem, The Raven (“But the raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only/That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.”) In numerous books and journal articles, linguists have tried, with various strange, gnarled compositions of letters to evoke the raven’s rich and textural voice. Robert MacFarlane uses gorrack gorrack (they always seem to be circling above him in his books) and anonymous experts on Wikipedia write their own attempts. Prrk Prrk. I found a YouTube video called Raven sounds creepy, ungodly, which might be one of my favourite film titles ever.

In February 2014, Jerwood Visual Arts announced that one of their two Open Forest commissions would be awarded to Chris Watson and Iain Pate’s remarkable proposal, to reinstate a raven roost, using ambisonics, into Kielder in Northumberland, the largest man-made forest in Europe. The other commission was awarded to Semiconductor, who I wrote about here.

In early February, before the announcement was made, I had a conversation with Chris about his proposal.

You are inviting people to come deep into the Kielder forest, to stand and listen to the sounds of ravens returning to roost. How do you imagine this will unfold?

The ravens come to roost at the end of the day, and although they are quite independent creatures, they do assemble en masse, and from a bioacoustic point of view, it’s believed that they exchange information about food and resources. In my proposal, while standing there, you’ll gradually lose what for most people is their main sense – vision – and I’m hoping that all the dark connotations of the forest, filled as it is with folk stories and myths and legends, will return to people while they are standing there.

The accompanying walk into the sound installation is also very important. You’ll walk up trails, through the mixed deciduous woodland, and then slowly enter the valley of the river Cottonhopesburn. There’s a mature conifer plantation, and by that point you’ll be into the darkest part of the forest, and it’ll loom all around you. We wanted it to be there because the sound changes, the acoustics of the forest change.

Then, we’ll cross a small stone bridge, quiet, and over the next fifty minutes, the piece will evolve. By that point, I hope that people will be tuned in to the natural sounds of the place. The idea of the piece is that the arrival of the ravens will be seamless with the already existing soundscape of the forest, and so darkness is innate to the whole process. After the piece finishes, people will be led out by torch light.

And what’s your own history with the ravens? Are these birds that you’ve recorded and listened to before?

In 2007 I had a commission from Bergen, in Norway, to make a piece celebrating the centenary of the famous Norwegian composer, Edvard Grieg. He famously documented local folk music, often writing it down in the cabin at the back of his house, which was a place where he was very much influenced by birdsong. The birds found their way into his pieces, but not in the way that they did in the composer Messiaen’s work, where he tried to imitate birdsong, but rather that Grieg was definitely influenced by his surroundings, and the voices of the ravens were prominent for him. In Norway, ravens are very powerful totemic birds. Like in the story of Odin suggests – where the Norse god sent his two ravens across the world to collect information for him – the Norwegians still have a lot of respect for ravens. They’re unique in that they span both the animal world and the spirit world.

Later, almost out of coincidence, I was travelling in Ethiopia, where the white-necked raven are often found nesting in the stone-carved churches in Lalibela. After that, I was recording a festival in Timkat, and I learnt from the local people that ravens are also regarded there as powerful spirit birds. They kept cropping up! I went to a sacred mountain in Japan, where I did a residency at the Kitakyushu centre for contemporary art, and there again there were fascinating stories about ravens. Here in this country, there are ravens in the Tower of London, but nowadays they have to clip their wings apparently if they fly away, the monarchy will fall…

In a lot of places they’re seen as birds of evil omen, particularly in Scotland, because they would stalk the battlefields and feed on the carrion of dead soldiers. Much earlier in Scottish and Norse mythology, they were also seen as birds that would carry the spirits of dead people into Valhalla.

But under all this rich mythology and legend, and on a much simpler level, they just have remarkable voices.

Studies of their voices suggest that they demonstrate ‘object displacement’ – that they can communicate about things distant in time and space, which only bees, humans and ants are proven to do. To return to the mythology, and particularly the Odin narrative which has circulated from as early as the 5th century, early cultures imagined that ravens were able to reap information, and to retell it. It seems as though myth might have quite accurately prefigured what science would later confirm.

Quite often, folklore is surprisingly accurate, and based on fact, because people generations before us were much better at listening. To give an example from my own experience: when ravens find a food resource, whether it be a grain store or a dead animal, the next day there might be 20 ravens back there, but never more than the amount of food that’s available. They are obviously sharing information, not only about the location of it, but how much there was. That’s incredibly sophisticated, like the waggle dance in bees. Ancient societies could obviously hear the rhythms of their voices, and interpreted that something more complex was occurring.

Time is a key element in your proposal too: mythical time returns and bleeds into contemporary narratives; ancient time, and the cyclical time of the ravens returning each year to roost all gives a powerful sense that we are only fleeting visitors, temporary in this world. Your proposal seems to emphasise this.

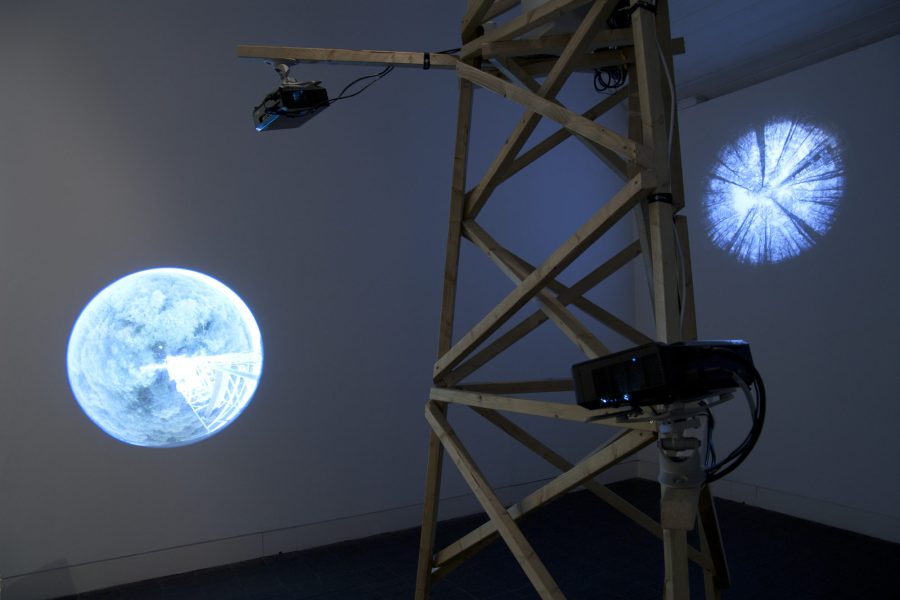

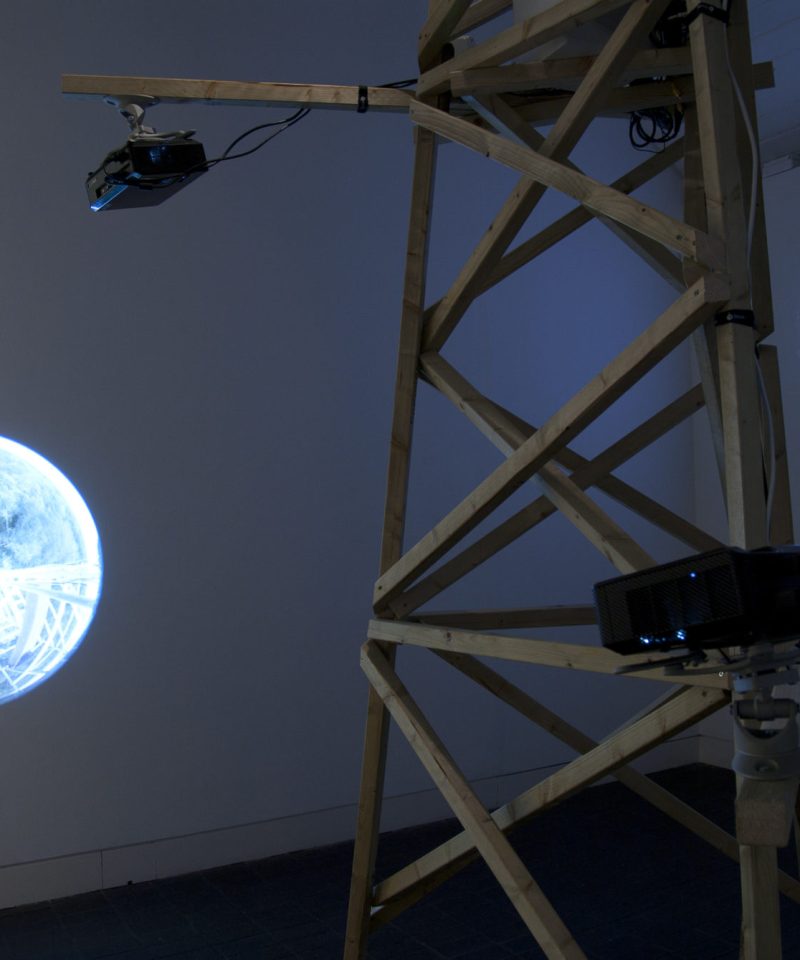

That’s a very good summation of my thoughts, in many respects. The whole point of the piece is that from the moment people cross the bridge into the raven roost, by the very look of the place – the tall mature trees, and because the speakers are placed high-up in the canopy – it will sound like ravens in the halls of Valhalla. It will have a cathedral-like acoustic. I hope that it will send a tingle down peoples spines, that it will activate an innate sense within us, an animal instinct, of being in the dark, being rather at a disadvantage, but hearing the birds that have been in the forest for thousands of years, having a conversation directly overhead. At first, you might be anxious, unsure, but you re-emerge slightly altered, along with others, collectively, and then go and resume your normal life. I like that idea of a changing process.

It feels like the kind of listening you are encouraging – an embedded, close-listening of the landscape – is an ancient practice. Today, we’re completely submerged in sound, but it’s very hard to listen.

As a species, we’ve evolved with such sophistication because we’re good listeners. It was vital to our survival. What’s happened now is that we’re bombarded by sound and noise, and so we no longer get an opportunity to listen, or to interpret it. If you ring your bank, they’ll play music at you. There are constantly aircraft above us – helicopters, planes, computers, lighting systems. We spend a lot of time, negative energy, processing power, shutting these things out, simply to concentrate on our day-to-day life. But if you take people to a place where they can really open their ears, it becomes a very creative function. You start to tune in and it engage your brain in a different way – it stimulates the limbic region of your brain, which is linked to creativity, emotion and memory. So this isn’t a soporific exercise. It’s something we need. It’s not an artistic whim, we need to listen for our psychological health and wellbeing.

Quietness is paramount to creativity. A place to go and rest your thoughts.