I am sitting in a corner of the gallery. My legs that are encased in light grey jeans are stretched out to make a line that is then extended by the dark grey slate tiles and from these, the dark grey object. An editor of an art magazine is taking notes when I arrive, and admires how the floor and sculpture are tonally working in tandem. He doesn’t know that soon my limbs (and language) will become part of the fixture, too.

Typing in this floor position, I am the figurative intruder, filling out the institutional void, and embodying it with material substance. My writing body feels exposed – even though he has now left – as my fingers scuttle across the keys and singular words emerge, in black, on the fake white page. The object stays rooted to the floor (like a tree-trunk, and like my bum) but its lines move: its surface pattern stages action and performance, a nod to the busy bodies that made it. I imagine a swarm of hands clutching pencils and rulers, slinking down the vertical surface and getting physically close to it. This grey and green sheet of two-dimensional surface, and patternised resistance, is a singular monolithic disguise for background teamwork.

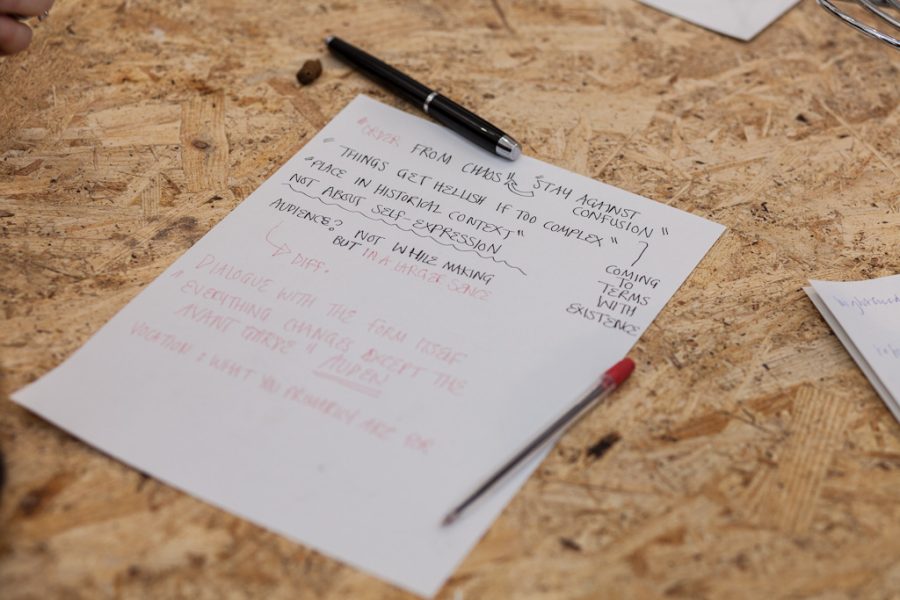

KB. I told them not to worry too much, not to stress over every mark, which gave a lot more rhythm to the drawing. I wouldn’t stand there watching but I would change people around every ten or twenty lines, to give it a bit more texture.

I am writing a diary out of, through and on the work, inscribing and annotating in ad-hoc fashion, just like the workers who drew onto it. We’re both sensing the material; feeling it as we go. The first time I saw the work I couldn’t stop moving about the room, making my own foot-stepped lines, to view and concentrate on it from different angles, and now I’m making different kind of lines, moving trapeze-like across the keyboard. With my eyes tied to the work and the words, it’s a balancing act of looking, reading and writing.

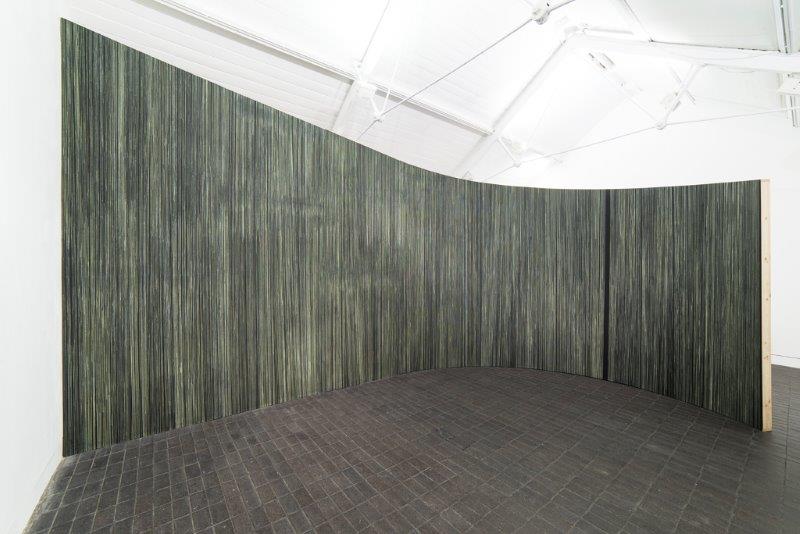

I am visible but veiled at the same time. Velum is a curved sculpture that carves the space in two, protecting my private from the outside public. This artificial wall separates the exterior from the interior, the skin from the membrane. The title of the work Velum shifts in meaning in the same way as its quivering string-bound aesthetic moves and shakes (it looks like it could be plucked like a violin). Incurring rhythm and noise. I wonder what it would be like to pluck language, its phonemes spiralling from a linear system.

Velum is veil; it is bodily tissue; it is muscle: it is paper. Never one, or the other, but a frenetic experience of them all. From the reference to the inference to the metaphor. I start to wonder that the work is much more corporeal than it first appears, alluding to a phantom body, or perhaps the gallery intruder herself.

KB. I like words and titles that have double meanings and the potential of that: it forces the viewer to inspect the work more closely: then you can see it is really made out of thin MDF and is not actually calfskin vellum at all.

I entered this veiled space from behind (from backstage), its naked construction exposing itself before the main event. This backwards path made me feel curious, unknowing, vulnerable and visible: it is a trick to surprise us. I had to question what it even was to start with, intuit its material substance: is it rope; is it collage; is it curtain… is it flesh?

KB. It feels more three-dimensional here because of how you approach it, which is important, as it allows the audience to move around the work and explore it.

Velum is a serpentine wooden structure that bends, concave, like a river. It is huge, nearly as high as the ceiling at one end, before decreasing with the curve to a smooth horizontal edge lower than its starting point. This wooden room divider is about twenty centimetres thick, as in three-dimensional, but it performs like a piece of paper – although is in no way flat. Velum contains, and then exposes, a two-dimensional surface that urges you, I, anyone, to touch it. Feel it. Climb all over it and make your own mark with dirty thumb-prints. Doing the wrong thing. I wonder at Velum’s precarious existence, a solid but also ephemeral object.

KB. It’s really robust even though the surface is really delicate. It’s odd that I don’t feel that precious about it; maybe I just got rid of that, and let go, when I knew other people were touching it, smudging it, drawing on it.

It is a stage for drawing two-dimensional light green vertical lines, in all kinds of thicknesses and angles and wayward ripples, hidden amidst the discipline. From grey to green to black to yellow. From a thread to a void. The line is not a homogenous mark, however clean and simple it appears. Accidents happen on this stage. People forget their lines. They become interrupted or change direction, if only by a degree. In this wall of self-imposed excess and regularity – a formula, essentially – it is easy to get lost. It is easy to find pleasure in the tidal marks and constellations that happen and move in and around the order. I find myself desiring the unruly (even if ‘ruled’) lines, the scars that stray from the formula of linear inscription.

Velum makes contact with the viewer, and talks to her: asks her what it means to look.

KB. It was quite important to me that you could become immersed in the drawing: that it’s the only thing you can see.

As it screens out the background faces to only let in background noise, Velum constructs a curiously intimate space for writing, an invitation for a body to inhabit. Once the man leaves, for the most of the day I am the only body in the room, this busy screen of corporeal gesture and willed physicality (it takes muscular effort to draw these lines) inviting wild and automated acts of typing. If writing is meant to be a private experience in which you get to know oneself, in this walled room, I am partly private and partly public. I am intimately public.

KB. The work surrounds you: it gives you the privacy you need, to look.

To write in and with Velum is to combine acts of seeing, with acts of desire and language, in the middle of a public space. Constantly navigating what it means to be not just a body, but also a writing body, in a room. On the edges of visibility, flirting with risk. I thought I would feel self-aware but Velum, in its curved wing-like hold, is cradling: it understands what it means to write, and what writing needs. What this space needs. I look at it from a side-ways angle, and wonder if it is also a giant scroll, in a constant process of unfolding. Its marks could be words, its linear gestures an ambiguous and personal language.

This diary-like text was formed from a conversation with Kelly Best, and notes made in front of the artwork at Jerwood Space, 15 June 2015. An in-conversation with Kelly, Georgie Grace and the editor and critic, Oliver Basciano, happened later in the day, incidentally also in front of Velum.

Velum was commissioned through Jerwood Encounters: 3-Phase, a new artist development collaboration between two artist-led organisations Eastside Projects (Birmingham) and g39 (Cardiff), and Jerwood Charitable Foundation, through its London based gallery programme Jerwood Visual Arts.