Hands are not neutral appendages. They shape and alter what they touch, leaving residues of sweat, salt and DNA; expose the fragility of protected things; surround static objects with choreographies of encounter and display; reveal the continuity of material culture through time (in touching an ancient artefact, you are, in a sense, ‘touching the past’); suggest the presence, and absence, of gendered authority; and portray the human body in ambiguous relation to the things it seeks to possess and protect.

All of these resonances are at play in the work of Kate Morrell, a multi-disciplinary artist who produces books, sculptures, installations – and drawings. Throughout her work there is an emphasis on tactility, from the uncoated paper stock and risograph ink of Alpine Spoilers, which emphasise the textural pleasures of handling books, to her Stone Axes (Group II), which with their scalloped ridges and handy sizes suggest an ancient ergonomics translated into contemporary materials.

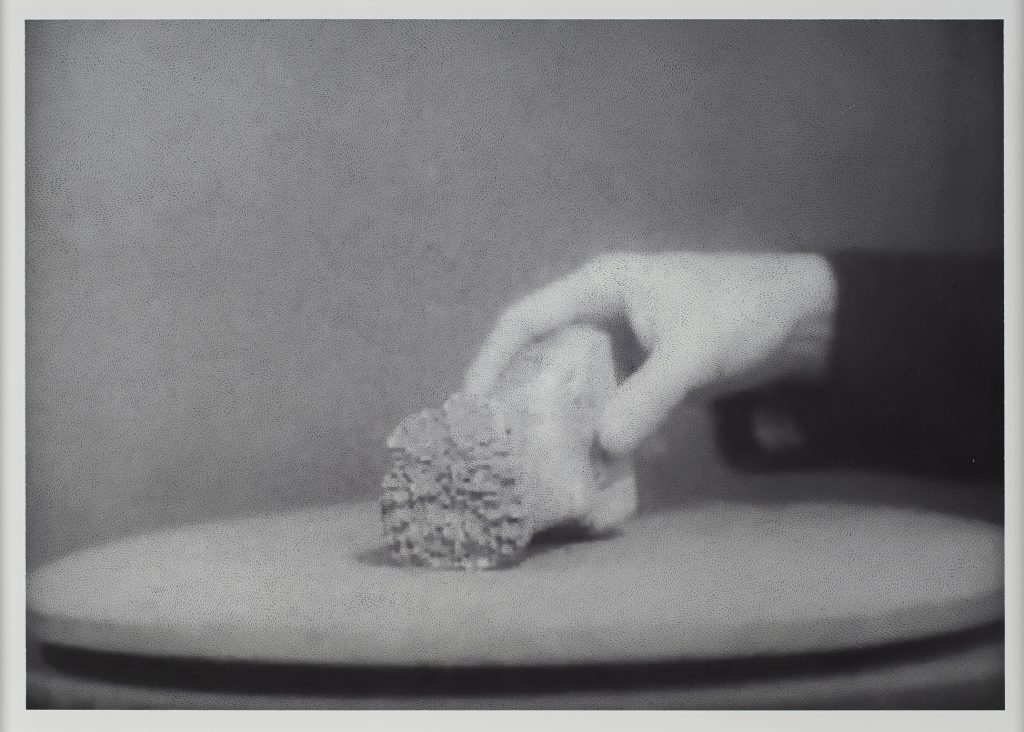

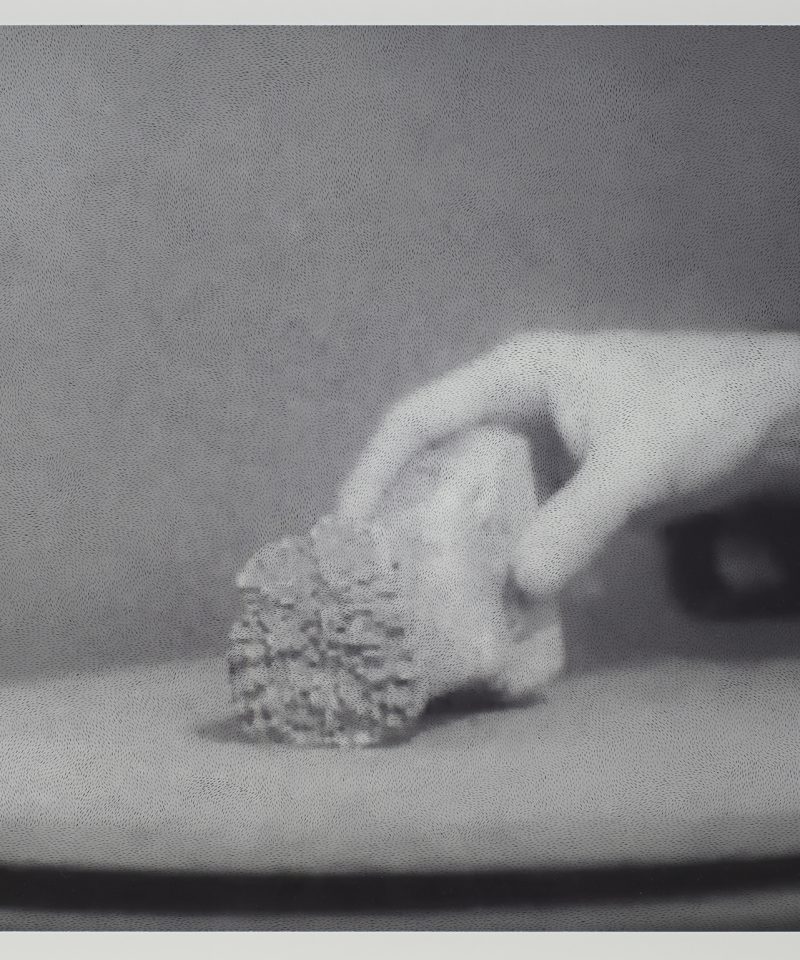

Her piece selected for the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014, A.V.M, 1954, Screenshot 2013-12-10, is one of the reasons I’ve chosen to pursue the theme of hands. The deep ambiguity of the image – this ghostly, black-clad figure emerging from the right of the frame to put down (or pick up?) what appears to be a fairly plain, unremarkable chunk of rock – invites multiple readings. This complexity or uncertainty of perception is underscored by the pointillistic technique the artist has used. Seen from across the room, the picture has a soft and hazy, almost underwater appearance; up close, however, the image resolves into billows and gusts of tiny black marks of extraordinary precision. These marks enhance the Giclée-printed image across which they move, but also suggest a newly mediated encounter with the source material, distorting what is brought to light. The nested histories the drawing contains – the ancient world of the artefact itself; the TV programme in which the object is displayed; and finally Kate’s present-day (for the time being) drawing – are connected by the presence of hands: hands that sculpt, handle and draw.

I spoke to Kate via email.

Firstly, I’d be interested in hearing how the A.V.M. drawing sequence came about. What drew you to the subject? Did it emerge from ongoing research, or a chance encounter?

The work is part of a series of four drawings which were made for the solo exhibition Pots Before Words at Gallery II, University of Bradford. The project was the result of my research within the Jacquetta Hawkes Archive, which is held at Special Collections, University of Bradford. Hawkes (1910-1996) was a writer and archaeologist who played an important role in popularising archaeology through her writings and radio and TV appearances. Much of the work produced for my show focussed on Hawkes’ interest in prehistory, and her humanist approach to archaeology. There are images of the show on my website.

The screenshots are selected from early episodes of a BBC panel show produced around the 1950s. It was one of the first examples of archaeology within popular media and Hawkes was one of the few women to appear on the programme as an expert in her field. The programme featured a panel of male ‘experts’ and a female assistant, or object handler. Objects were displayed on a slow-turning circular display wheel. Through the process of logical thought, experts identified the objects for the audience. Other than her hands and wrists, the female assistant is never shown.

I was interested in the different ‘handlers’ within the show and their role in the production of object-meanings. I found the handling by the silent assistant quite compelling – particularly these performative (but un-choreographed) gestures for display and interpretation that were created.

In the series, three of the drawings feature the (female) assistant, and one drawing shows the (male) archaeologist reaching into shot, to remove the object from the display wheel for inspection. Only the male hand features in the Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014 exhibition. It’s a shame all four drawings were not able to be shown.

It would be good to hear a little about the experience of making the drawing. How long does each drawing take, for example? What is it about this specific way of working that appeals to you?

The drawings are roughly A2 size. They are made with drawing ink and paintbrushes used for miniature painting. Each drawing took around 20 hours to complete. I used 7 paintbrushes to make the series – each one was eventually discarded once it begun to disrupt the uniformity of the lines. I might have achieved greater precision with a technical drawing pen, but I like the fact that brush and ink reveals evidence of the hand, and tools, used in the process.

I’m quite conscious of the time invested in drawings. In the previous blog post you talk about ‘the work of art as a vessel of invested time, the lasting relic of ephemeral gestures’, which I think resonates with this series too.

Are you interested in this relationship between tactility implied by the image of hands, and the tactility of drawing?

A few (fragmented) thoughts:

I think this tension between protection and possession, implied by object handlers in the drawings, is also reflected in the archaeological approach to excavation and collecting. Archaeologists aim to protect and preserve, but the act of excavation itself can be destructive. It’s interesting that people who care for archives are often called the ‘keepers’ of a collection.

In handling, objects become free from their fixed interpretations assigned within static museum displays. In the process of scientific interpretation, the knowledge of the past is undergoing continuous reconstruction. The repetitive drawing technique has a transformative quality. I wanted it to depict these object-meanings to be in a state of flux.

The brushes used to make the drawing indicates the microscopic, scientific lens and a transformation of matter under close scrutiny. Lithic drawing is used by archaeologists as a process for recording finds. When illustrating stone tools, the structure of the rock, including its tactile ripples and fractures, are documented using finely-drawn black lines. It’s thought to be one of the best ways to understand the method of its production (other than through flint knapping). I think it’s an interesting use of drawing within a scientific discipline – one that relies upon direct handling and re-interpreting.

Alongside this idea of drawing as a kind of science, I wonder if you would consider your drawing sequence as a form of ‘interpretation’, another ‘layer’ in the histories of these objects?

Yes, drawing is used to add another layer to the interpretation of objects, although I didn’t want the new layer to feel fixed or definitive. Much of the original image remains under the shadow.

Is there a connection between the A.V.M. drawings and your earlier sculptural work Flint? The markings on the surface of this work are quite similar.

I began the Flint series in 2010. The markings are quite similar, but they are applied to the surface of large pieces of flint stone. They both demonstrate the transforming quality of this repetitive drawing method. This additional layer of interpretation both overwhelms and enhances the original surface markings.

Do hands appear in your work more widely?

I’m planning to make a new piece of work using a stone turntable I produced: Lazy Susan: Portable Toolkit. It’s a stone apparatus which functions as a portable, table-top display. I’m going to approach various archives and collections with the sculpture, in order to play host to a series of female archivists and archaeologists and the chosen artefacts of their profession. Objects will be re-animated by the hands of archaeologists, geologists and archivists and the object presentations will be filmed.

In this context, the Lazy Susan device is a counterpart to the potters wheel – on both surfaces, matter is re-modelled, displayed and performed.

Are you also drawn to more recent non-archaeological examples of ‘handling’ and display? I’m thinking in particular of infomercials and game shows, which often feature (silent) female assistants.

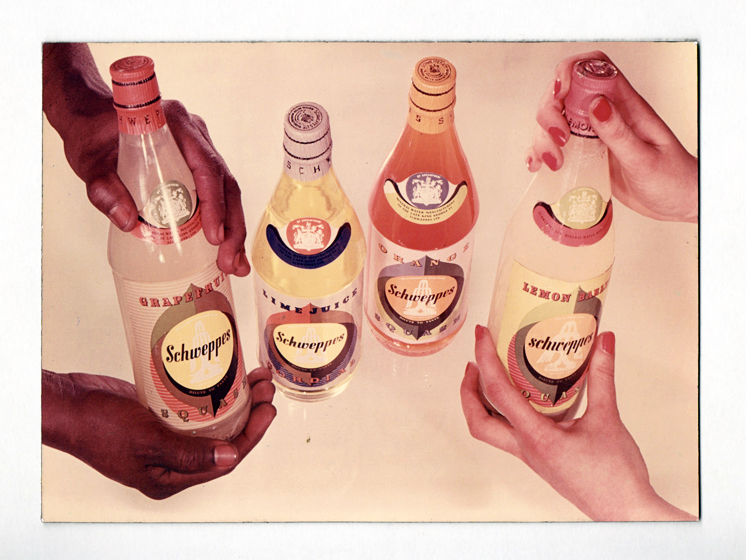

The (mostly unintentional) humour of these outdated formats appeals to me. The lo-tech lazy susan device still makes appearances on these game shows too.

I also look out for instances within printed matter, although I don’t see many contemporary examples in print. Below is an image that I picked up at a car boot sale. It was part of a portfolio of advertising images by an unnamed photographer.