I am not a maker. Like others my understanding of materials is aesthetic: formed by haptic, physical and sensorial experience that has developed into embedded memories of objects and surfaces. My knowledge of making is vicarious, learned through watching, reading and listening. Thinking about how materials are formed fills me with the same feeling I had during most maths and physics lessons in secondary school: a kind of detached wonder that makes my brain float and my body distant. I imagine procedures that probably could not happen, but without any attempt or desire to make them a reality. Sites of industry are for me, as for many others, mysterious places, disconnected from a present where surfaces are coated, veneered and anodised.

Until recently I sat next to artist Ruth Claxton for 2 days every week at Eastside Projects. For me and many of Birmingham’s younger artists Ruth is a font of making knowledge. She is someone who has learnt partly through trials in her practice and partly through more formal training previously available in the form of City & Guilds courses. This type of knowledge, embodied and learnt through activity, is very different to mine. I could ask Ruth questions like: what actually is shellac? And which metals can you weld together? Of course Ruth doesn’t know everything but she has routes to finding out most things. Along with Architects Alessandro and Mike Dring and musician and print maker Sean O’Keeffe, Ruth is planning Birmingham Production Space, a national site for making, both digital and analogue.

I inhale parts of the research undertaken by the artists I work with and thus have a rock-pool-like picture of materials and processes, with areas of shallow and slightly deeper understanding. Recently I have spoken extensively about casting, a process that endlessly fascinates all sorts of practitioners and which (like developing photographs) uses a mesmerising process of reversal. Casting formed the basis of one of the most enchanting artist talks I have encountered, given by artist Florian Roithmayr at the brilliant production site Grymsdkye Farm in August 2014.

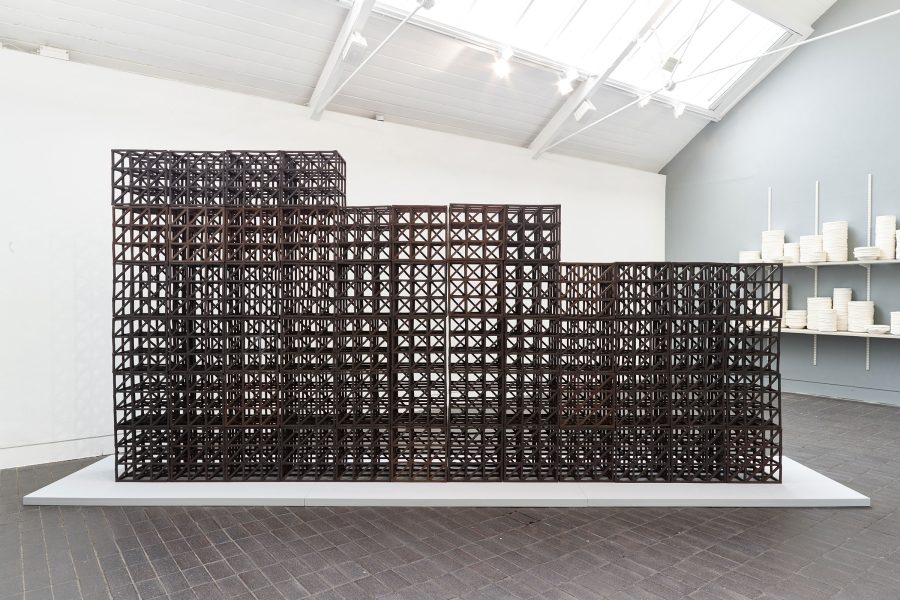

Conversations with artists Marie Toseland and James Parkinson have triggered much of my recent thinking on casting. Both are currently showing cast works (in ceramic and glass and plaster respectively), in a group show I curated at The Sunday Painter, Peckham. For Marie casting is an intimate, erotic process wherein the original or container is suffocated by the substance filling it and eventually replicating it; whereas for James it is a system of loops and references through which he can explore the space between the actual and the virtual to look at notions of representation, embodiment and provenance.

I often think about the origins of, and journeys undertaken by, matter. The recent trend in tracing the lives of materials and objects (think Jane Bennett, Maurizio Boscagli, Mark Miodownik, OOO) has perhaps refreshed my interest in this, which began when I was an undergraduate student in social anthropology. I think too about how the politics of materials is formed by processes of extraction and the environmental and human costs incurred. I wonder if we will come up with a way of manufacturing some of the rare minerals that we currently depend on for our well-loved smart phones and tablets, whether we can produce them in a laboratory as we are now able to produce diamonds, or whether this will come with its own substantial problems. The V&A’s current show, What is Luxury, poses many interesting questions around the production of value through the employment of time, skills and expertise and rare materials.

At a recent conference on production, Fran Edgerley, a member of Assemble, proposed that production is an opportunity for people to be involved in productive activity, and noted the phenomenon of social prescription whereby GPs prescribe activity to aid all sorts of issues including depression and addiction. This reminds me of the meaningful activity utilised in the field of Occupational Therapy and brings me to an internal debate I have been having about the contemporary push for mindfulness and wellbeing. With the Conservative party’s Budget having been announced only 2 days ago, the idea that those who do not engage in normative, healthy, happy working lives are not of value or interest to society is fresh in my mind and I feel increasing scepticism seeping into my understanding of Britain’s new-found ‘understanding’ of mental health issues.

From this position of commissioning and curating as a way of questioning and absorbing knowledge (and let’s not forget that writing and curating are a processes of making and shaping material too) I find myself newly part of a group of people looking after a collection at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, which is comprised in part by twentieth century ceramics and a significant collection of contemporary jewellery. As such I have begun to swat up on studio ceramics practice and to learn about the field of contemporary jewellery, which I have to say is more interesting and political than I previously imagined (my limiting preconceptions showing).

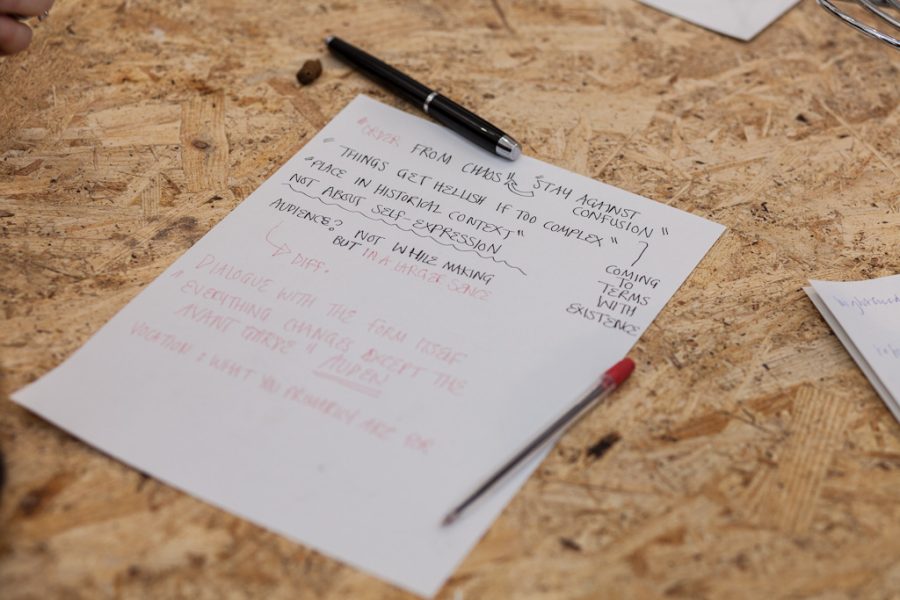

These are the references that form my thoughts on Friday 10 July as I travel to London to see the Jerwood Makers Open 2015 and meet some of its makers the morning after it opened. The posts that follow will reflect on some of the threads initiated above.