Until being selected for the Jerwood Makers Open you were making small items of jewellery. What prompted you to up-scale your work and start creating these quirky interactive sculptures?

I really enjoy making and the exciting thing about jewellery is that, in a sense, it’s interactive. Jewellery is never complete until worn by a moving, animated person; its on the body that these small, sculptural objects come alive. Jerwood Makers Open gave me the chance to take this idea to the next level and create sculptural objects that have a life of their own. Financially, I had been previously restricted in size, and JMO allowed me to take risks and create larger, more complex work. In a way it was easier for me as I genuinely don’t distinguish between these two ways of working; jewellery is small scale sculpture worn on the body, and the interactive pieces are objects adorning the space.

Tell me about the organic forms you’ve created. Are they inspired by the natural world? They look like the kind of thing you might see under a microscope.

My goal in terms of form was to create objects that could be from the natural world. I think too much Computer Aided Design looks mathematical and very artificial so I aim to create objects that although unrecognisable, appear familiar, like a creature from deep under the ocean, or a specimen found on a nature walk. I am also fascinated by microscopic images of pollen.

You use rapid prototyping to create your works. Could you explain exactly what this is and how it works? It sounds pretty complicated!

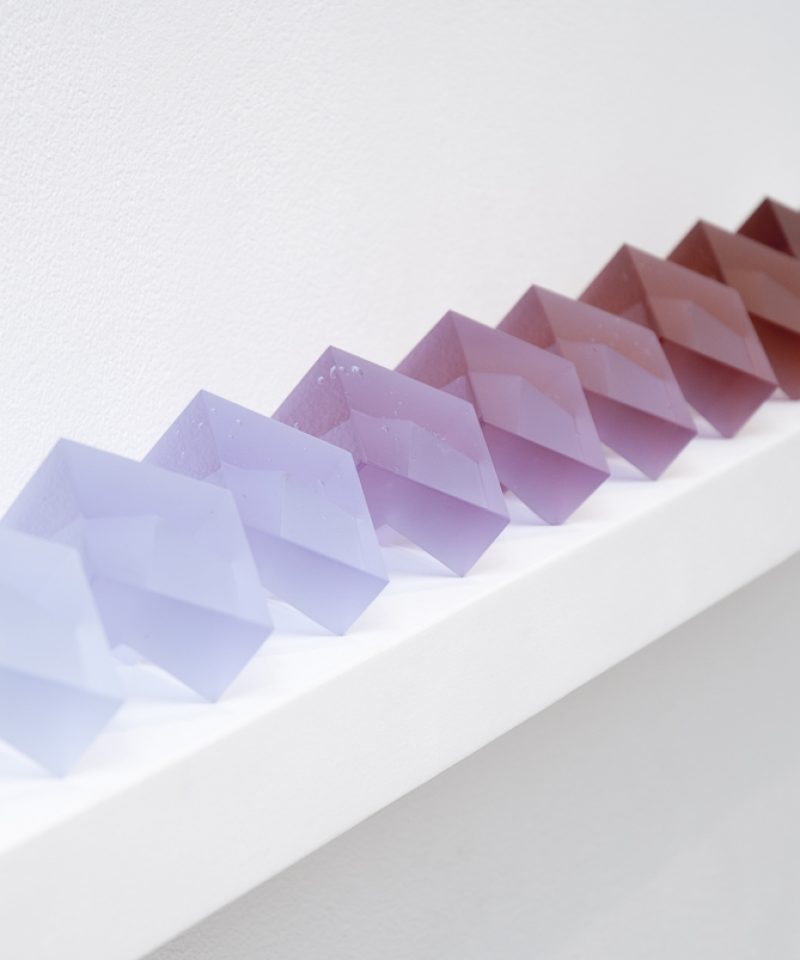

Rapid prototyping is made up of two subtypes: additive processes, where material is added to build up a form, like a potters wheel, and subtractive processes, where material is cut way, like a stonemason carving away to reveal form. I work with additive processes like selective laser sintering and stereo lithography. This means I draw the object using CAD packages like Rhino and Cloud9, and then upload the file to a 3D printing service, such as Shapeways. They use a computer programme to slice the object into fine layers and this information is put into a machine that builds the actual object. Using selective laser sintering, powdered material is fused together layer by layer with a laser, which builds up the object. The larger, coloured bits of my sculptures are made this way using powdered nylon. I love the matt, velvety texture of the nylon. Steriolithography is then used to set a light-sensitive gel using a laser; the areas hit by the laser harden to create the form. As with any making process, rapid prototyping has its own restrictions and rules. Although I would love to have my own 3D printer, they are rather expensive, and this means relying on an external body to make the work. Also ‘rapid’ is a relative term; sometimes it takes two to three weeks for pieces (particularly the larger ones) to be made.

The works seem very technical. Did you have to learn a lot about electronics to accomplish these pieces?

I’d never made anything interactive until the Jerwood Makers Open. It was an extreme learning curve (and I’m still learning!), and at times quite stressful. I’m very grateful to my friend, Andrew Simpson, who, having studied electronic engineering, explained the basics of electronics to me, and helped me out with the more fiddly bits of soldering and setting up components. I couldn’t have done it without his helping me make sense of things. I tried to do as much as possible on my own, which probably wasn’t the best idea because I’d have to learn what could be done, and then find out how to actually do it. From a technical point of view, none of the sculptures were very complicated, I struggled more with making the interaction fluid and sophisticated rather than than the actual nuts and bolts of it.

Do you consider these works as sculptures, craft or something else? Where do you think the boundaries lie?

I struggle with labels. I’d much rather have people interact with the work and be immersed in it without nitpicking over categorising it. I think this attitude perhaps affects the work I create; it’s very much on the boundary between several disciplines. I like to describe them as interactive objects, and leave the categorising to the audience. I appreciate that different people will approach the work as sculpture, or craft, or large scale jewellery, or a very expensive one-of-a-kind toy depending on their own background.

When I first encountered Quiver it made me really nervous; it’s not every day that an artist allows you to handle their work in a gallery. Are you concerned that the piece might get damaged?

Perhaps it comes from my jewellery background, but I like the idea of encouraging audiences to handle, even play with works in a gallery. This is something I struggle with when I go to galleries and museums; my hands itch to touch, and not being able to makes the experience very sterile. The body of work for the Jerwood Makers Open was dreamed up as a way of setting that idea on its head, so not only are you allowed to handle Quiver, but your experience of it isn’t actually complete until you pick it up, turn it over and feel it vibrate and purr in response. The work is designed to be robust enough to cope with this interaction and hopefully will be easily fixed if it does break, but it’s difficult to plan for all eventualities when making interactive things. Although it is more of a risk that the piece might get damaged because the audience is allowed to handle it, the work becomes quite pointless without that risk. I could hardly say ‘it’s interactive, it’ll respond if you pick it up, but please don’t in case it breaks!’

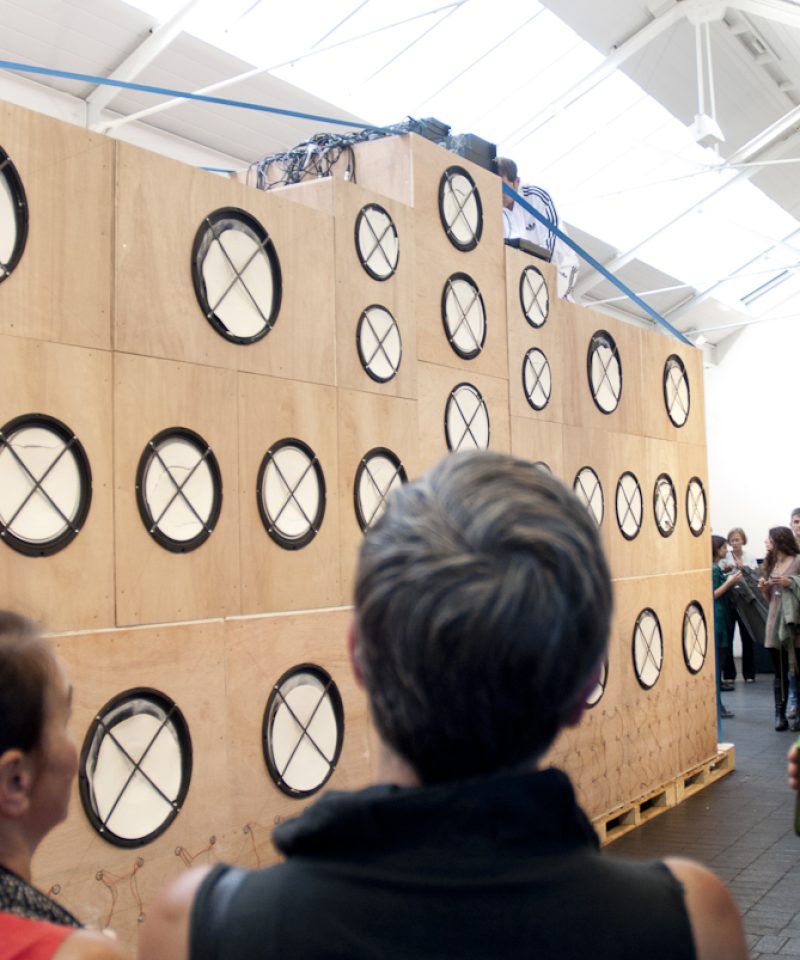

Where did the idea for Bristle come from? It’s almost like there’s a creature living in there.

FB: Bristle is my favourite of the works; it seems to respond to interaction in such a temperamental way. The idea evolved out of a combination of things. After designing Quiver I knew I wanted to create something that responded to movement. Also, I suffer from depression, and do have days when I feel exactly like Bristle; vulnerable and shy, wanting to keep the world at a distance to protect myself. Extruding spikes seems the best way to express that feeling! I like to think that a lot of people feel a similar way, from the attention Bristle got on the opening night. I think the fact that you don’t know exactly what sets the sculpture off adds a live quality to it — you never know what it might decide to do next!

David Trigg: Until being selected for the Jerwood Makers Open you were making small items of jewellery. What prompted you to up-scale your work and start creating these quirky interactive sculptures?

Farah Bandookwala: I really enjoy making and the exciting thing about jewellery is that, in a sense, it’s interactive. Jewellery is never complete until worn by a moving, animated person; its on the body that these small, sculptural objects come alive. Jerwood Makers Open gave me the chance to take this idea to the next level and create sculptural objects that have a life of their own. Financially, I had been previously restricted in size, and JMO allowed me to take risks and create larger, more complex work. In a way it was easier for me as I genuinely don’t distinguish between these two ways of working; jewellery is small scale sculpture worn on the body, and the interactive pieces are objects adorning the space.

DT: Tell me about the organic forms you’ve created. Are they inspired by the natural world? They look like the kind of thing you might see under a microscope.

FB: My goal in terms of form was to create objects that could be from the natural world. I think too much Computer Aided Design looks mathematical and very artificial so I aim to create objects that although unrecognisable, appear familiar, like a creature from deep under the ocean, or a specimen found on a nature walk. I am also fascinated by microscopic images of pollen.

DT: You use rapid prototyping to create your works. Could you explain exactly what this is and how it works? It sounds pretty complicated!

FB: Rapid prototyping is made up of two subtypes: additive processes, where material is added to build up a form, like a potters wheel, and subtractive processes, where material is cut way, like a stonemason carving away to reveal form. I work with additive processes like selective laser sintering and stereo lithography. This means I draw the object using CAD packages like Rhino and Cloud9, and then upload the file to a 3D printing service, such as Shapeways. They use a computer programme to slice the object into fine layers and this information is put into a machine that builds the actual object. Using selective laser sintering, powdered material is fused together layer by layer with a laser, which builds up the object. The larger, coloured bits of my sculptures are made this way using powdered nylon. I love the matt, velvety texture of the nylon. Steriolithography is then used to set a light-sensitive gel using a laser; the areas hit by the laser harden to create the form. As with any making process, rapid prototyping has its own restrictions and rules. Although I would love to have my own 3D printer, they are rather expensive, and this means relying on an external body to make the work. Also ‘rapid’ is a relative term; sometimes it takes two to three weeks for pieces (particularly the larger ones) to be made.

DT: The works seem very technical. Did you have to learn a lot about electronics to accomplish these pieces?

FB: I’d never made anything interactive until the Jerwood Makers Open. It was an extreme learning curve (and I’m still learning!), and at times quite stressful. I’m very grateful to my friend, Andrew Simpson, who, having studied electronic engineering, explained the basics of electronics to me, and helped me out with the more fiddly bits of soldering and setting up components. I couldn’t have done it without his helping me make sense of things. I tried to do as much as possible on my own, which probably wasn’t the best idea because I’d have to learn what could be done, and then find out how to actually do it. From a technical point of view, none of the sculptures were very complicated, I struggled more with making the interaction fluid and sophisticated rather than than the actual nuts and bolts of it.

DT: Do you consider these works as sculptures, craft or something else? Where do you think the boundaries lie?

FB: I struggle with labels. I’d much rather have people interact with the work and be immersed in it without nitpicking over categorising it. I think this attitude perhaps affects the work I create; it’s very much on the boundary between several disciplines. I like to describe them as interactive objects, and leave the categorising to the audience. I appreciate that different people will approach the work as sculpture, or craft, or large scale jewellery, or a very expensive one-of-a-kind toy depending on their own background.

DT: When I first encountered Quiver it made me really nervous; it’s not every day that an artist allows you to handle their work in a gallery. Are you concerned that the piece might get damaged?

FB: Perhaps it comes from my jewellery background, but I like the idea of encouraging audiences to handle, even play with works in a gallery. This is something I struggle with when I go to galleries and museums; my hands itch to touch, and not being able to makes the experience very sterile. The body of work for the Jerwood Makers Open was dreamed up as a way of setting that idea on its head, so not only are you allowed to handle Quiver, but your experience of it isn’t actually complete until you pick it up, turn it over and feel it vibrate and purr in response. The work is designed to be robust enough to cope with this interaction and hopefully will be easily fixed if it does break, but it’s difficult to plan for all eventualities when making interactive things. Although it is more of a risk that the piece might get damaged because the audience is allowed to handle it, the work becomes quite pointless without that risk. I could hardly say ‘it’s interactive, it’ll respond if you pick it up, but please don’t in case it breaks!’

DT: Where did the idea for Bristle come from? It’s almost like there’s a creature living in there.

FB: Bristle is my favourite of the works; it seems to respond to interaction in such a temperamental way. The idea evolved out of a combination of things. After designing Quiver I knew I wanted to create something that responded to movement. Also, I suffer from depression, and do have days when I feel exactly like Bristle; vulnerable and shy, wanting to keep the world at a distance to protect myself. Extruding spikes seems the best way to express that feeling! I like to think that a lot of people feel a similar way, from the attention Bristle got on the opening night. I think the fact that you don’t know exactly what sets the sculpture off adds a live quality to it — you never know what it might decide to do next!