The text is the first sign that we are on retrofuturist time – it’s the unmistakable green terminal font of an obsolete MS-DOS system, rolling out in a staccato rhythm across the bottom of the screen. Maybe it’s more memorable to us from late night reruns of Alien and Terminator than from the actual use of a vintage PC; personally I find the haptic experience of technology in memory seamless enough but I always remember movies. The terminal type, along with a synth-heavy soundtrack, is one of a few nods to bygone eras of the information age in Anna Bunting-Branch’s animated film The Linguists from a suite of works called The Labours of Barren House. It situates us in some approximation of the near future as ventured circa 1984 – but it’s a schizoid, palimpsestic near future also somehow redolent of lace-strewn Victoriana too. Maybe it’s one re-imagined eighties hypothesis of the current day. Relative to the eighties, the current day is indeed the near future, but it’s not the present – something crucial is missing, something disappeared down fiction’s slipstream between the future of then and the present of now.

The retrofuture of The Linguists isn’t casually invoked for nostalgic millennial lolz. In fact it’s sacred, it’s a site of ritual, a site for the creation of meaning, for transformation and transubstantiation. It’s full of symbolically charged images like the melting wax of a red candle, blood and lipstick merging in a single, protean, magical unguent. The remains of a dismembered marble statue are anointed with red kisses on her eyes, the thumb and forefinger of her hand making a workable mouth, on her pubis where they form symbolic labia. The red lip impressions assume the power of speech, joining the votaries in chorus, voicing the stone body to life. Obvious differences aside, not least its theological origins; the scenario is not unlike that of the Golem, the clay man of Jewish folklore. Our statue becomes sentient by the singular devotional power of the word – here spoken, in the Golem’s case written. He has a Shem (any one of the Kabbalistic names for God) written on a piece of paper and placed in his mouth by a Rabbi to animate him – removal of the Shem condemns him back to earthen inertia.

The strange, distinctly Gaelic/Brittonic sounding language spoken throughout the ritual of The Linguists is Láadan. This was the brainchild of science fiction author Suzette Haden Elgin. She sought to construct, in full, a language that truthfully represented the perceptions and experience of women in a way that already established languages could not; established languages being patriarchal as they constitute and are themselves, constituted by, the organizing principles of the dominant power – they are its means and its end.

In the canon of languages custom-made for speculative fiction, Láadan might have ranked alongside Tolkien’s Elvish or Star Trek’s Klingon as an ambitious and rigorous undertaking to fabricate another world in the round. Láadan’s ambition, however, is significantly broader, its purpose being not merely to support a fictional universe where beings communicate in ways that we don’t understand but which are linguistically consistent. Its purpose was to address one of the most overwhelming yet fundamental entreaties of the feminist project: that is to answer the question, can patriarchy be unlearned? If it can, and here’s where things can become fatally problematic, from whom will all the women of the world, with their varied experience and perspectives, be expected to unlearn it?

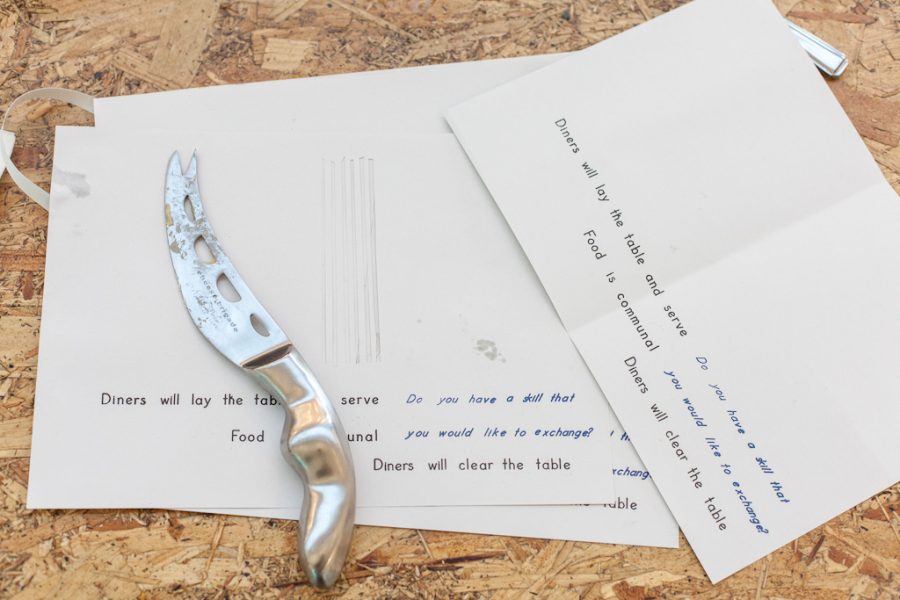

Elgin released the first of her Native Tongue novels – the series for which Láadan was conceived – in 1984. She had gone straight to the heart of her matter and authored the language before the fiction that would be its vehicle. Native Tongue is set in a dystopian future after women’s suffrage, along with a swath of other attendant rights have been revoked. Women have, again, been relegated to a state of near absolute servitude to and dependence upon men. In correlation with grotesque gender inequality, there’s a caste like system of social stratification whereby a powerful but solitary society of linguists maintain a monopoly on interplanetary economic relations, owing to their rarefied gifts as translators of extra terrestrial languages. In a Barren House – where women of the linguist class are sent beyond child-bearing age, for a lifetime of talking and knitting and doing nothing important – a revolutionary endeavour is secretly underway: Láadan, the language that could loosen the male stranglehold on power. It seems appropriate that the management of such a concept would become the responsibility of the vanguard of the imagination – the storytellers. Science fiction or speculative fiction, in particular, makes sense as it’s understood more clearly in the field that a proposed scenario is formulated more as a question than an answer. In Elgin’s own words, Láadan was a ‘thought experiment’ – one that, in time, she came to regard as failed.

The Linguists also addresses a renewed interest in Witchcraft as a working model for feminist organisation and praxis. This interest acknowledges the pariah status granted the practice throughout history by, often malign, paranoid and intrinsically misogynistic fictions. The motif of the coven – of small groups of women integrated within a wider network, communicating in an inaccessible (to men) vernacular – has always had a special place in the cherished hatreds of patriarchal power. The Linguists here draws parallel to more secular practices associated with activism local in its action and global in its scope: The forum of the consciousness-raising group, for example. To the reactionary mind, the method of consciousness-raising unites two, apparently contradictory dysfunctions of radical praxis – factionalism and groupthink, as though neither ever played any substantive part in realpolitik. This enmity may be partly semantic – people seem less averse to the term ‘think tank’, perhaps because it’s named after something hard.

But the exchange of ideas in a ritualised durational fashion impacts our social reality all the time, from parliamentary activity to international trade – these rituals, for better or worse, are the very bricks and mortar of social transformation, which usually begins in microcosm and must happen by exchange, not design. Maybe that was Elgin’s error – Láadan was arrived at a priori. That being said, she made it clear that she expected corrective responses. Native Tongue, then, was meant to open rather than close a conversation. Two years after Elgin’s death and twenty five since the last of novel in the series was released, with The Linguists, Anna Bunting-Branch has added to a rich dialectic that some might have been thought vestigial except that, fortunately, that’s not how the exchange works.