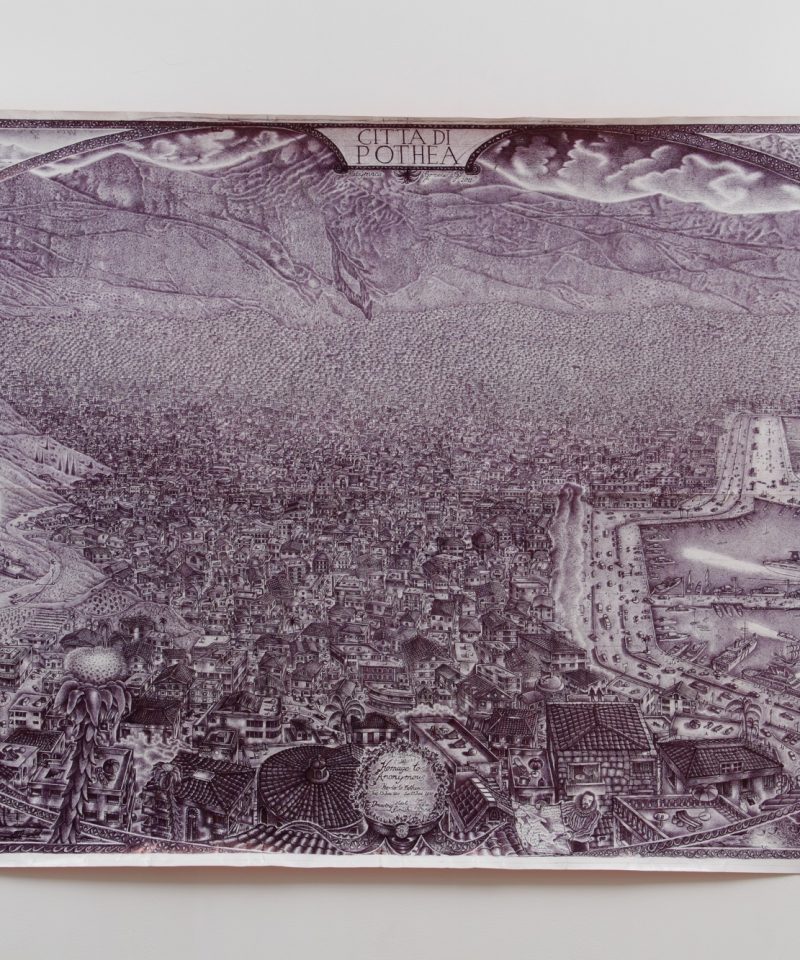

I wanted to end my extended and erratic notes on this years’ Jerwood Drawing Prize by looking at Karen Blake’s Walking Classes video in the show. A split screen show on one side a bird’s eye map, the other a blank chalkboard. The time of day ticks by on the bottom left of the screen, joined by various job descriptions and personal entities: street cleaner, postman, mother and children. As each comes up, a line starts to etch it’s way through the street map. Correspondingly, a left hand uses a piece of chalk to follow the trail of lines. The dark trails on the street map fade as they finish, but the ‘actual’ drawing on the right accumulates the marks, becoming an abstract shape in itself. What interests me is that the right half of the screen- the chalk drawing- is ‘the drawing’, but the piece dissects itself by showing the provenance and build up of its essential parts as well.

Made using GPS following people who walk in the Peckham area, Blake seems to be making an implicitly political statement – the approximate rhyme of the title with ‘working classes,’ the choice of people followed on their routes being more socially inclined, from a leaflet distributor to a traffic warden to a social worker. It maps when these people are active, but also suggests through literally overlapping other potential crossovers. Interestingly, for example, the trail of the artist we follow intersects with the vicar and the community warden.

The piece came out of previous works with GPS, exploring boundaries and concepts of home that then pointed to the independent provenance of the floating, cybernetic line made by the device that existed in a sort of non-space but still existing in time. This led to working with walkers, finding particular, regular routes and exploring the relationship and correlation with their actual route and the satellite-created one. Drawing the routes, re-enacting them with the body, then becomes a way of re-placing them on a human scale.

In Blake’s own words:

The idea of re-drawing the lines as a compilation came initially as a corrective. Surprisingly ( and reassuringly?) satellites don’t track some movements through a space very accurately. This led me to think about actuality and virtuality and how tangled up they are becoming. By re-versioning the lines, I could highlight the discrepancies being thrown up by the digital lines. It also allowed me to realise the interconnections that the walkers couldn’t know. A hand drawn line becomes more accurate than the virtual one.

The piece originally was projected on the floor, about 1m x 2m, as in the image below, in what might make more of a retinal dance between the different modes of moving, tracing and mapping. The overall perspective of the piece – seen from above, it’s relentless distance and abstraction- could be a paranoid Enemy of the State-like statement, but the small monitor screen showing of it keeps its sketched-out, informal qualities.

What Blake deposits as drawing, here, is something communal – though defined by a particular range of community (‘those who perambulate’). It is an abstract portrait of Peckham, and while what determines the lines is the artist – her walking with these people – the resulting line drawing is more like the notion of a ouija board, the hand being guided by these people. Drawing here, then, is also an almost subconscious event. It could be seen as a Rorschach image of sorts, the subliminal picture the movements of an area create; speaking of the piece, Blake mentions a bit in Paul Auster’s City of Glass, 1985, where a private detective follows a man through the streets of New York, the man providing clues by spelling out letters with his trail through the city’s grid. But Walking Classes also provides a vision of drawing where the image itself is irrelevant, subsumed by the process, and where the hand of the artist is an analogue for a digital trace and another, absent, event.